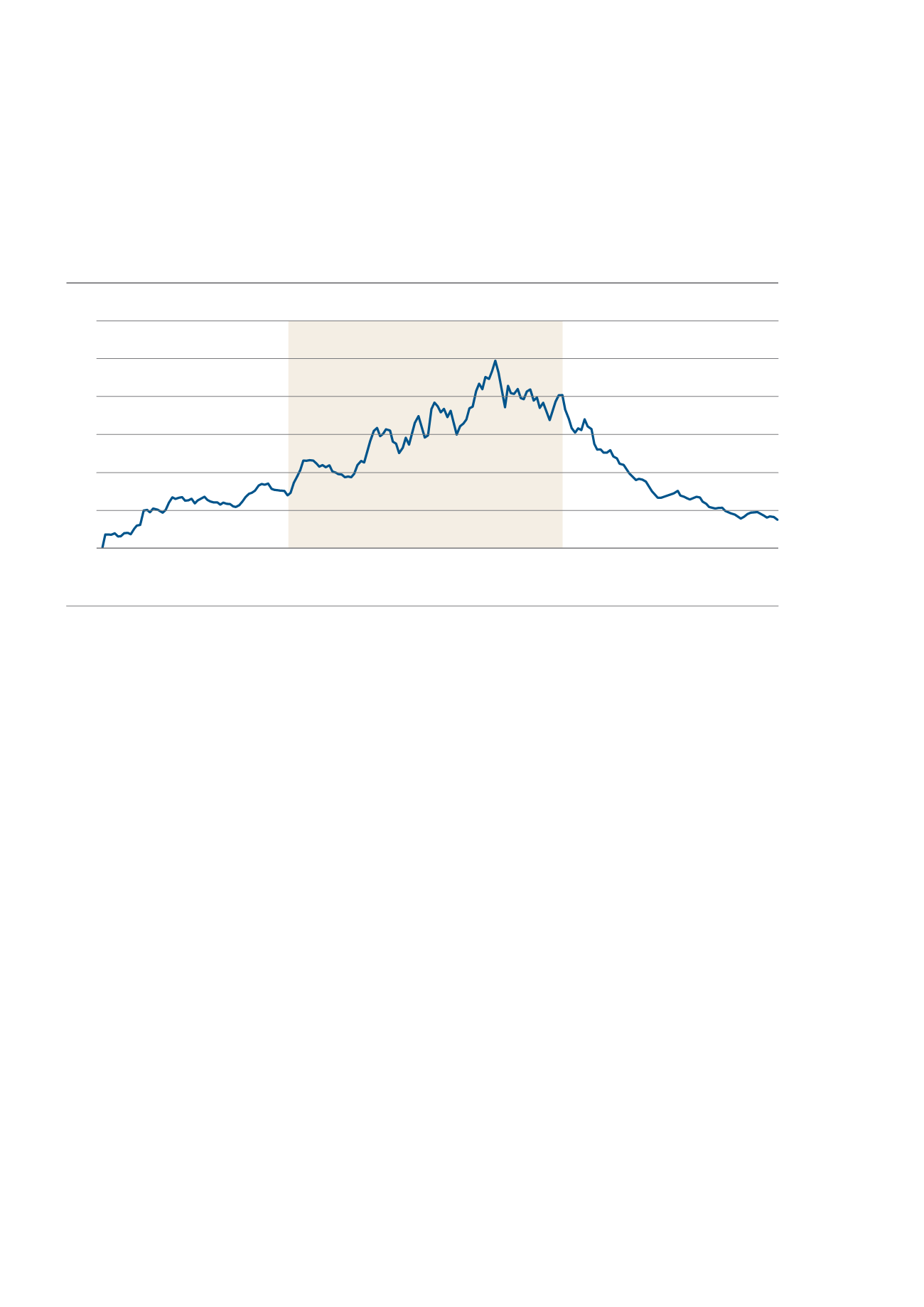

3

1700

1750

1800

1850

1900

Industrial Revolution (1760 –1840)

Debt over nominal GDP, in %

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

Fig. 1

Long-term evolution of Britain’s government debt

mining, and transportation – were more or less cut

off from the standard funding sources, i.e. from

both credit and capital markets. On top, prejudices

against these new technologies and their representa-

tives prevented the rich upper class from invest-

ing their money in some more direct form in these

new sectors. These enterprises thus had to largely

finance themselves, even though their rate of return

increased from 10% (1770) to 20% (1830) and was

thus much higher than in the two dominant asset

classes of the time – land and government bonds.

So far, so bad. However, in this state of dysfunction-

al credit and capital markets, it was the fast-rising

market for government bonds that was at least able

to help the entrepreneurs in an indirect way, namely

through the labor market. The argument runs as fol-

lows. Traditionally, the main holders of the national

wealth, the upper class, invested in land and its cul-

tivation. With a return on investment of about 2%,

this was not profitable, but status in England was

always directly coupled with land ownership.

Due to the higher returns on government securities

and their increasing availability and liquidity, the

majority of the upper class changed their invest-

ment strategies around 1750. They did not continue

investing in the purchase and maintenance of land,

but in government securities that promised a higher

yield, reducing the extent of the chronic excess

investment in the farm sector. This decreased labor

opportunities and wages in the farm sector, leaving

large numbers of agricultural workers unemployed,

forcing them to move away from the countryside

into the cities in order to find work in industry.

While difficult for laborers, this was good news for

the industrialists. As they suddenly had a large num-

ber of cheap laborers available for the new factory

jobs, their production costs fell as a result of lower

labor costs, and their profits rose accordingly.

Due to the inability to raise funds in capital and

credit markets, it was the reinvestment of exactly

these profits in their own enterprises that kept this

new emerging sector afloat. In the presence of this

dysfunctional financial sector, the rapidly increas-

ing state debt, which created a new large and liquid

investment class in the form of government bonds,

therefore supported the process of structural change

away from less productive agrarian activities into

new, more productive industries. And it was pre-

cisely these new industries that spearheaded the

most fundamental structural change in history,

namely the Industrial Revolution that originated in

eighteenth-century England and thereafter started to

spread around Europe, and then around the world.

Good and bad debt

History thus shows that under particular circum-

stances, high debt levels may not be a stumbling

block for economic development, but may even

enhance it. Based on this insight, Voth advocates

developing a more unbiased approach towards

sovereign debt, one that not only considers its dan-