8

Abstract

The creeping hollowing out of the middle class and the simultaneous rise of automation have become hotly debated topics in the popular media and among policymakers, and there is certainly no shortage of dire predictions about the ascent of robots and subsequent obsolescence of workers. But – doomsday prophecies aside – what are the facts? What is happening to workers, specifically middle-class ones? And, from a policy perspective, what can (or should) be done to address this fundamental shift in who – or what – does which jobs?

This Public Paper tackles these questions head-on. We first identify the types of individuals who are likely to work in middle-class occupations and track how they act on the labor market outcomes. Then we evaluate policies proposed in recent years that have been aimed at combating the labor market malaise middle-class workers have experienced.

The creeping hollowing out of the middle class and the simultaneous rise of automation have become hotly debated topics in the popular media and among policymakers, and there is certainly no shortage of dire predictions about the ascent of robots and subsequent obsolescence of workers. But – doomsday prophecies aside – what are the facts? What is happening to workers, specifically middle-class ones? And, from a policy perspective, what can (or should) be done to address this fundamental shift in who – or what – does which jobs?

This Public Paper tackles these questions head-on. We first identify the types of individuals who are likely to work in middle-class occupations and track how they act on the labor market outcomes. Then we evaluate policies proposed in recent years that have been aimed at combating the labor market malaise middle-class workers have experienced.

Video summary

Job polarization and policy approaches

Over the past four decades, technological advances such as computing, robotics, and artificial intelligence have substantially changed labor markets. These advances, while making us more productive, have also modified and altered the types of jobs we do.

In this same time period, the US economy and other industrialized economies have seen a sharp drop in the share of the population employed in middleskilled occupations. A growing literature shows that this employment loss is linked to the disappearance of routine jobs, that is, those jobs for which tasks are repetitive and follow a set of clear instructions. These types of activities are, by their nature, highly vulnerable to takeover by new automation technologies.

Indeed, until the mid-1980s, about half of employment in the US was concentrated in routine occupations, while that fraction has fallen to one-third today. The collapse of employment in routine occupations, which tend to be middleclass jobs, is known as “job polarization.” Job polarization is defined by observed growth in either the highskilled, high-paid and the low-skilled, low-paid categories, and a shrinking of the middle-skilled, middle-wage jobs category. These dynamics have led the middle class to experience a hollowing out in terms of wages and employment opportunities.

As an example, consider the birthplace of modern American automobile manufacturing. At the beginning of the 20th century, Henry Ford revolutionized the factory floor and helped create an industry that would support generations of middle-class workers. Several decades later in 1969, General Motors installed its first spot-welding robot, automating almost all welding operations. Thus, the industrial genesis of the middle-class also became ground zero for replacing workers with automation technologies.

This Public Paper’s goal is to enrich our understanding of the adjustment to this new economy by studying two integrated topics. First, the paper seeks to document in the empirical section how workers with “routine characteristics” have adjusted to these changes. For example, are these individuals now employed in other jobs? Do they tend to be more frequently unemployed? Or are they more likely to drop out of the labor force completely?

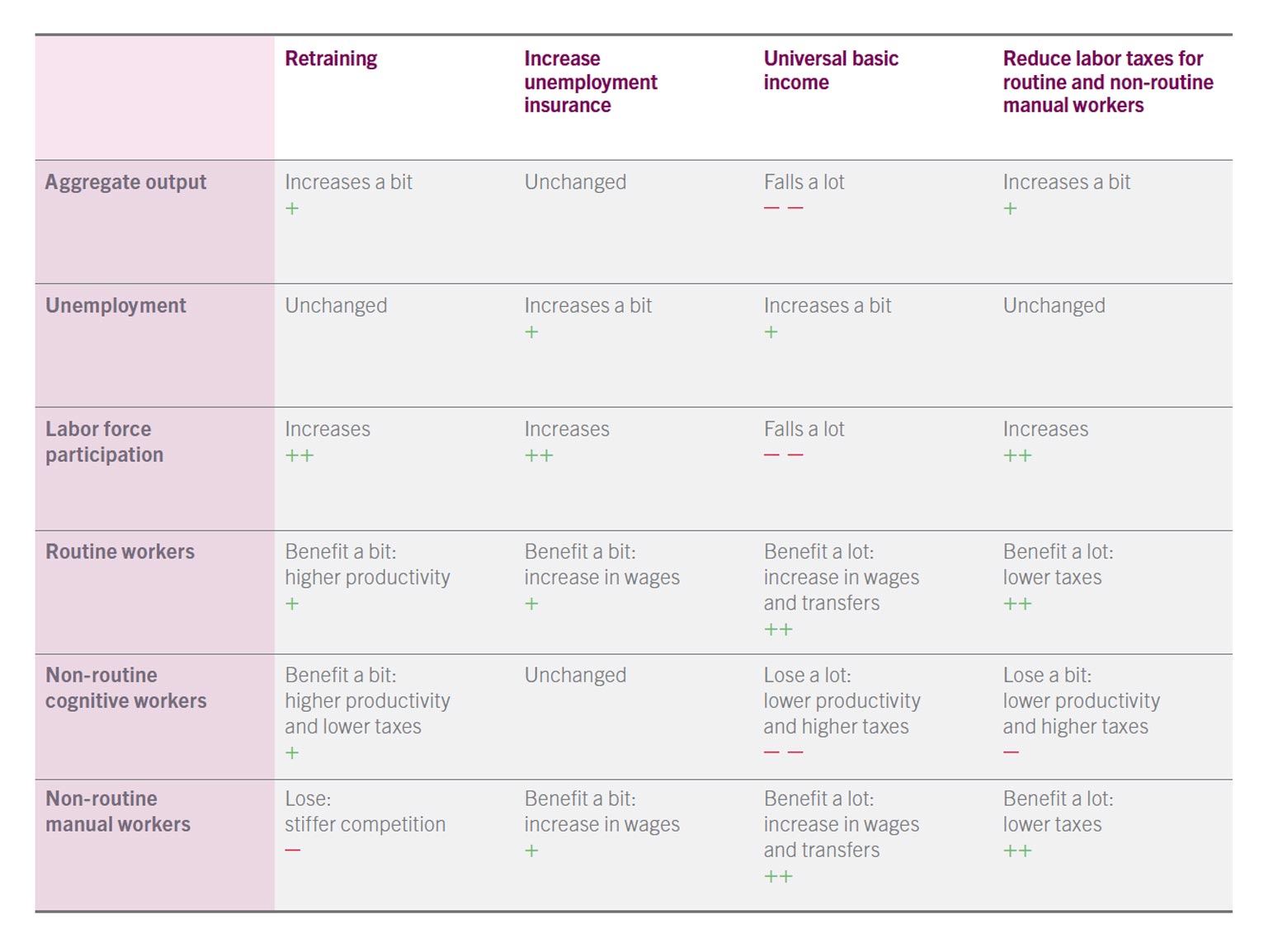

Second, the paper evaluates the most prominent policy proposals that have been recently proposed as part of the plan to address the demise of the middle class: a universal basic income, the reform of the unemployment insurance system, changes in the tax code, and the retraining of workers. We introduce a conceptual framework to evaluate the outcome of these proposals and to identify the potential winners and losers of each of these policy reforms.

Over the past four decades, technological advances such as computing, robotics, and artificial intelligence have substantially changed labor markets. These advances, while making us more productive, have also modified and altered the types of jobs we do.

In this same time period, the US economy and other industrialized economies have seen a sharp drop in the share of the population employed in middleskilled occupations. A growing literature shows that this employment loss is linked to the disappearance of routine jobs, that is, those jobs for which tasks are repetitive and follow a set of clear instructions. These types of activities are, by their nature, highly vulnerable to takeover by new automation technologies.

Effectiveness of different policies

The changes in the labor market that have occurred over the last few decades are most likely here to stay, if not to accelerate. Indeed, the discussion today has turned to how occupations that were previously thought to be immune from automation and digitalization are more likely to experience the same kind of cannibalization by automation technology that has already affected other routine occupations. Perhaps the impact of automation on labor opportunities depends on which of the following two possibilities will prevail. Will job opportunities simply vanish as automation takes over completely, or will automation enable us to specialize in tasks for which we have a comparative advantage, leaving the mundane, routine work to our robot replacements?

In the meantime, this Public Paper has attempted to explore and account for some of the key adjustments that workers with “routine characteristics” have made in response to increased automation in the labor market. In analyzing the potential economic effects of different policies currently under discussion, it becomes clear that – perhaps not surprisingly – there is no single “magic bullet” policy that will make everyone better off. Each policy we evaluated results in winners and losers and implies different consequences for the economy at large.

Further work is required regarding the evaluation of labor market retraining programs and the development of empirically relevant macroeconomic models that can be used for policy analysis.

These efforts are crucial both for helping policymakers evaluate the possible strategies for meeting the challenges which the rise of automation poses, and for safeguarding the ever-shifting future of middle-class labor market opportunities.

The changes in the labor market that have occurred over the last few decades are most likely here to stay, if not to accelerate. Indeed, the discussion today has turned to how occupations that were previously thought to be immune from automation and digitalization are more likely to experience the same kind of cannibalization by automation technology that has already affected other routine occupations. Perhaps the impact of automation on labor opportunities depends on which of the following two possibilities will prevail. Will job opportunities simply vanish as automation takes over completely, or will automation enable us to specialize in tasks for which we have a comparative advantage, leaving the mundane, routine work to our robot replacements?

In the meantime, this Public Paper has attempted to explore and account for some of the key adjustments that workers with “routine characteristics” have made in response to increased automation in the labor market. In analyzing the potential economic effects of different policies currently under discussion, it becomes clear that – perhaps not surprisingly – there is no single “magic bullet” policy that will make everyone better off. Each policy we evaluated results in winners and losers and implies different consequences for the economy at large.

Related press

Will the covid-19 pandemic accelerate automation? Economist 22.4.2020 read

Related videos

Author

Nir Jaimovich received his PhD from Northwestern University in 2004. He works on macroeconomics questions with special emphasis on business cycles, labor markets, and the macroeconomic implications of micro product level data and was head of the NBER price dynamics group (together with Bob Hall). Within these research areas, he combines new data and quantitative theories to tackle long-standing macroeconomic questions. In the area of labor/macro his work shows how demographic composition and occupation structure of the economy shape the dynamics of the business cycle. In addition, his work examines the empirical and theoretical plausibility of signals and uncertainty about future economic fundamentals functioning as important drivers of business cycles. Finally, his micro-pricing product-level data shows how actual firms’ pricing strategies shapes the insights regarding the extent that monetary policy has an impact on the economy. His work has found large resonance inside and outside academia and was featured within policy circles (such as White House official publications) and media outlets such The New York Times, Washington Post, The Economist, the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, Forbes, Swiss and German media.

Nir Jaimovich received his PhD from Northwestern University in 2004. He works on macroeconomics questions with special emphasis on business cycles, labor markets, and the macroeconomic implications of micro product level data and was head of the NBER price dynamics group (together with Bob Hall). Within these research areas, he combines new data and quantitative theories to tackle long-standing macroeconomic questions. In the area of labor/macro his work shows how demographic composition and occupation structure of the economy shape the dynamics of the business cycle. In addition, his work examines the empirical and theoretical plausibility of signals and uncertainty about future economic fundamentals functioning as important drivers of business cycles. Finally, his micro-pricing product-level data shows how actual firms’ pricing strategies shapes the insights regarding the extent that monetary policy has an impact on the economy. His work has found large resonance inside and outside academia and was featured within policy circles (such as White House official publications) and media outlets such The New York Times, Washington Post, The Economist, the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, Forbes, Swiss and German media.