3

Video summary

In a nutshell

No state can exist in the long term without effective taxation. To be able to execute its various roles, the state needs to acquire the capacity to enforce compliance with tax obligations. Taxation is particularly challenging in developing countries, since it is difficult for the governments to gain information about what taxable transactions occur in more informal economies. This does not only lead to large losses in government revenue, it can also create negative distortions in the economy. The pressing need to tackle tax evasion has led to growing interest in ‘third-party reporting’ – the verification of taxpayer reports against other sources.

This policy brief explores the potential of such an approach to improve tax collection – as well as its limitations. Evidence from Chile shows how the value-added tax (VAT) can facilitate tax enforcement by generating paper trails on transactions between firms. But third-party information is not a miracle cure against evasion. Its effectiveness can be severely reduced if the government's enforcement capacity is low or if taxpayers can make offsetting adjustments on other margins for which third-party information is not available, as a study from Ecuador shows.

No state can exist in the long term without effective taxation. To be able to execute its various roles, the state needs to acquire the capacity to enforce compliance with tax obligations. Taxation is particularly challenging in developing countries, since it is difficult for the governments to gain information about what taxable transactions occur in more informal economies. This does not only lead to large losses in government revenue, it can also create negative distortions in the economy. The pressing need to tackle tax evasion has led to growing interest in ‘third-party reporting’ – the verification of taxpayer reports against other sources.

This policy brief explores the potential of such an approach to improve tax collection – as well as its limitations. Evidence from Chile shows how the value-added tax (VAT) can facilitate tax enforcement by generating paper trails on transactions between firms. But third-party information is not a miracle cure against evasion. Its effectiveness can be severely reduced if the government's enforcement capacity is low or if taxpayers can make offsetting adjustments on other margins for which third-party information is not available, as a study from Ecuador shows.

Opportunities for action

1

Certain forms of taxation such as the VAT generate incentives for firms to produce third-party information on transactions between firms, which has the potential to increase tax compliance.

2

To be effective, the use of paper trails needs to go in tandem with strong auditing and enforcement capacities.

3

Enforcing formalization at the final stage of production might contribute to formalizing entire production chains.

1

Certain forms of taxation such as the VAT generate incentives for firms to produce third-party information on transactions between firms, which has the potential to increase tax compliance.

2

To be effective, the use of paper trails needs to go in tandem with strong auditing and enforcement capacities.

Conclusions

What does this imply for the role of thirdparty reporting as a tool to develop tax enforcement capacity? On the one hand, these results show that paper trails are not a panacea and not something that can be turned on and that become effective immediately like a light switch. On the other hand, third-party information can still play a very important role in a number of ways.

First, when some transactions and firms are compliant with third-party reporting, authorities can focus their scarce auditing resources on the rest of the economy. Second, the deterrence power of paper trails can be built and strengthened over time. When firms report more costs, they have more incentives to ask for receipts, thereby increasing the coverage of the paper trail. The more firms comply and the more transactions are covered by paper trails, the more credible it is that authorities will clamp down on the rest.

To build this deterrence power, it may be in the interest of tax authorities to only send a small number of notices of discrepancies in the beginning. With this, they have the capacity to follow up with enforcement on all taxpayers who do not respond to the notice or respond in a highly suspicious way (such as increasing costs by the exact same amount as revenues, as in the Ecuadorian experience). Over time, an increasingly larger share of taxpayers will respond to such notices, and so an increasingly large number of notices could be sent with a constant capacity for followup on non-compliers.

This UBS Center Policy Brief summarizes evidence presented in the following academic articles:

‘No Taxation without Information: Deterrence and Self-Enforcement in the Value Added Tax’ by Dina Pomeranz, published in the American Economic Review 105(8): 2539-69 in 2015.

‘Dodging the Taxman: Firm Misreporting and Limits to Tax Enforcement’ by Paul Carrillo, Dina Pomeranz and Monica Singhal, published in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(2): 144-64 in 2017.

‘Taking State-Capacity Research to The Field: Insights from Collaborations with Tax Authorities’ by Dina Pomeranz and José Vila-Belda, published in the Annual Review of Economics 11: 755-781 in 2019.

What does this imply for the role of thirdparty reporting as a tool to develop tax enforcement capacity? On the one hand, these results show that paper trails are not a panacea and not something that can be turned on and that become effective immediately like a light switch. On the other hand, third-party information can still play a very important role in a number of ways.

First, when some transactions and firms are compliant with third-party reporting, authorities can focus their scarce auditing resources on the rest of the economy. Second, the deterrence power of paper trails can be built and strengthened over time. When firms report more costs, they have more incentives to ask for receipts, thereby increasing the coverage of the paper trail. The more firms comply and the more transactions are covered by paper trails, the more credible it is that authorities will clamp down on the rest.

Callouts

In detail

Strengthening state capacity and the ability to effectively and fairly collect taxes is a key priority for many governments around the world. Modern states execute a broad range of roles, ranging from assuring security, rule of law, and building infrastructure to providing services in the areas of education and health, or social programs. To be able to effectively implement these policies, countries need to acquire the ability to enforce compliance with tax obligations.

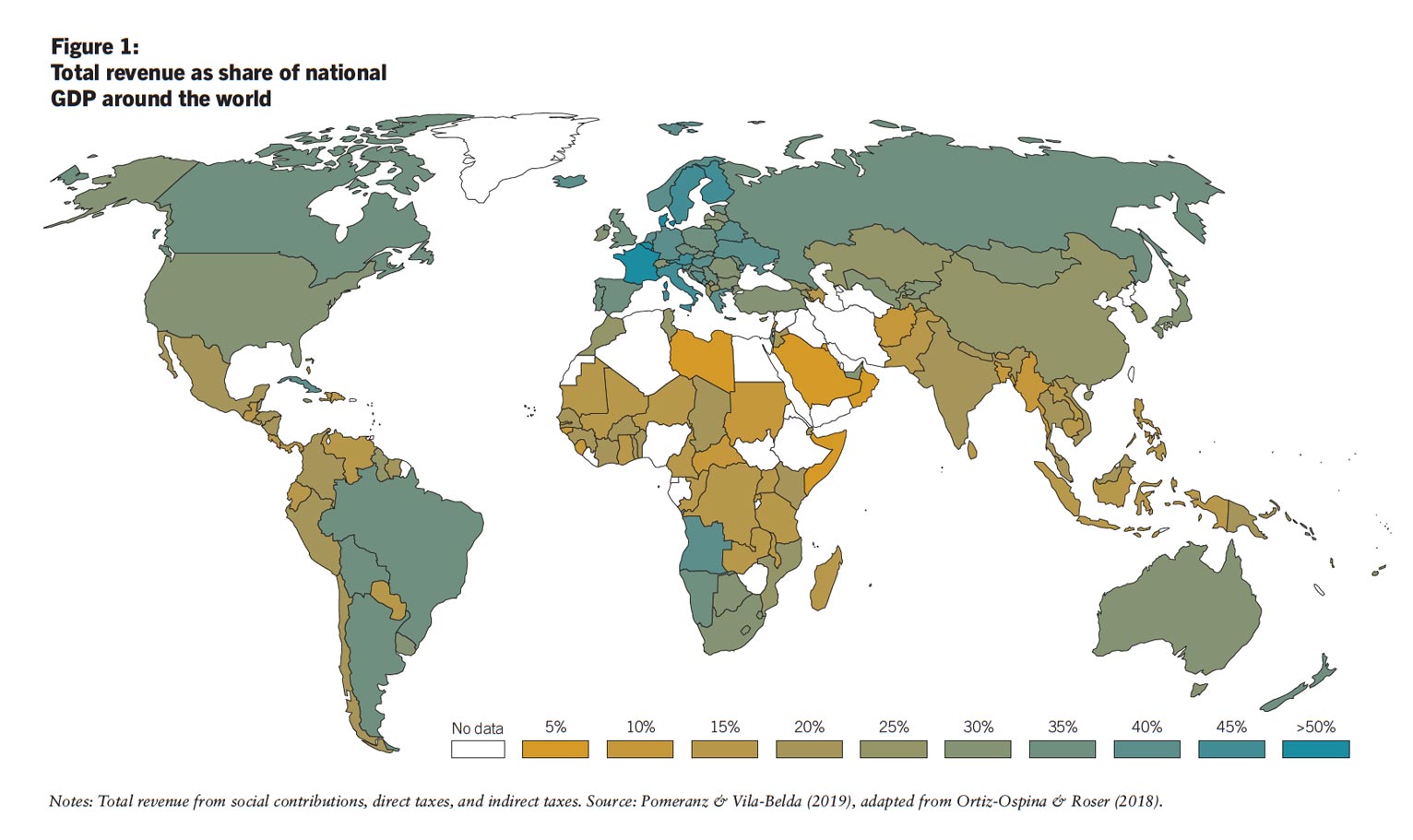

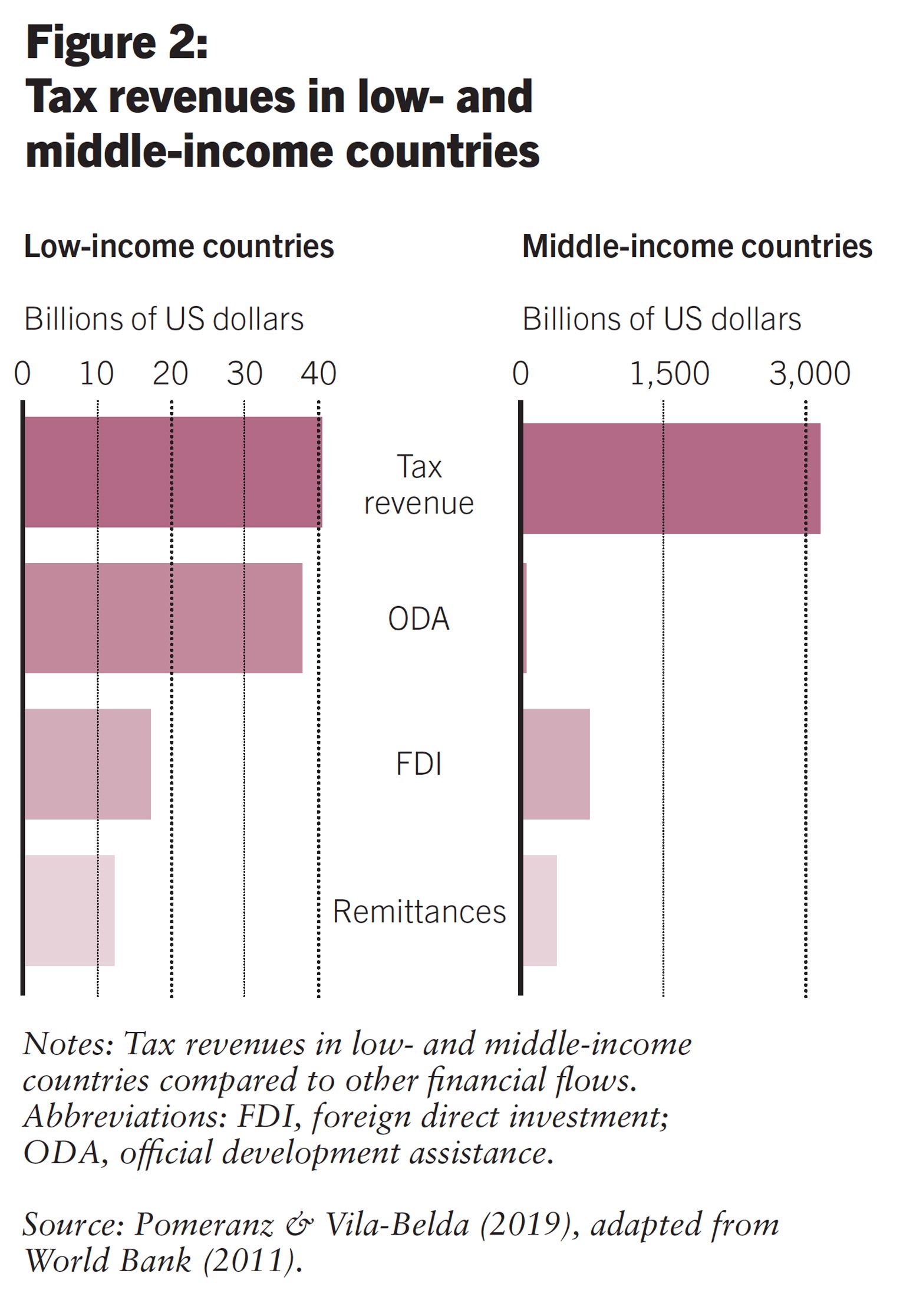

Low tax collection a century ago was not merely a political choice. Countries simply lacked the capacity for tax collection (e.g. Kleven et al. 2016). Throughout the twentieth century, most richer countries acquired a much higher tax collection capacity, and most high-income countries today have tax/GDP ratios between 25% an 50%. But countries with lower income per capita tend to have lower tax capacity and a smaller tax/GDP ratio (Figure 1). Combining a low GDP with less taxes collected as a share of GDP means the tax revenues are much lower than those in rich countries. In some countries, tax collection is smaller than international aid, and in low-income countries on average these two types of government revenue are of similar magnitude. In contrast, in middle-income countries, tax revenues are on average over 50 times larger than official development assistance (ODA), as shown in Figure 2. Raising tax collection capacity also allows countries to reduce their dependence on international aid.

Tax evasion is a fundamental challenge for developing countries, where the informal sector often accounts for a substantial share of the economy. Historically, governments have relied on audits as a way to enforce tax compliance (Allingham and Sandmo, 1972). Recently, alongside the global revolution in information technology, governments are increasingly turning to ‘third-party information’. This involves verifying taxpayer reports against other sources, such as employer reports of salary and VAT invoices, as a cheaper and more scalable tax enforcement strategy (Kleven et al, 2011; Naritomi, 2016).

Can tax policies that rely on third-party information improve tax collection in developing economies? I have explored this question in two recent studies in Chile and Ecuador.

Chile: deterrence and selfenforcement in the VAT chain

One of the key challenges in tax administration is that, to impose any tax, the state needs information about the taxable transactions taking place in the economy. This is particularly difficult in less developed economies, where many firms are not registered, and even among registered firms, a substantial share of transactions remains informal. Governments in these countries therefore tend to have much less information about taxable transactions (e.g. Gordon and Li, 2009 and Kleven et al., 2016).

Recent research collaborations with tax authorities have therefore focused on evaluating mechanisms aimed at increasing the information to which the tax authority has access. One key source of information in this context is “third-party reporting” (e.g. Kopczuk and Slemrod 2006, Gordon and Li 2009, Kleven et al. 2016). Such reporting happens when an agent in the economy has an incentive to report information to the government that includes evidence of a tax obligation by another agent. This then creates a paper trail of information that the government can use for tax enforcement.

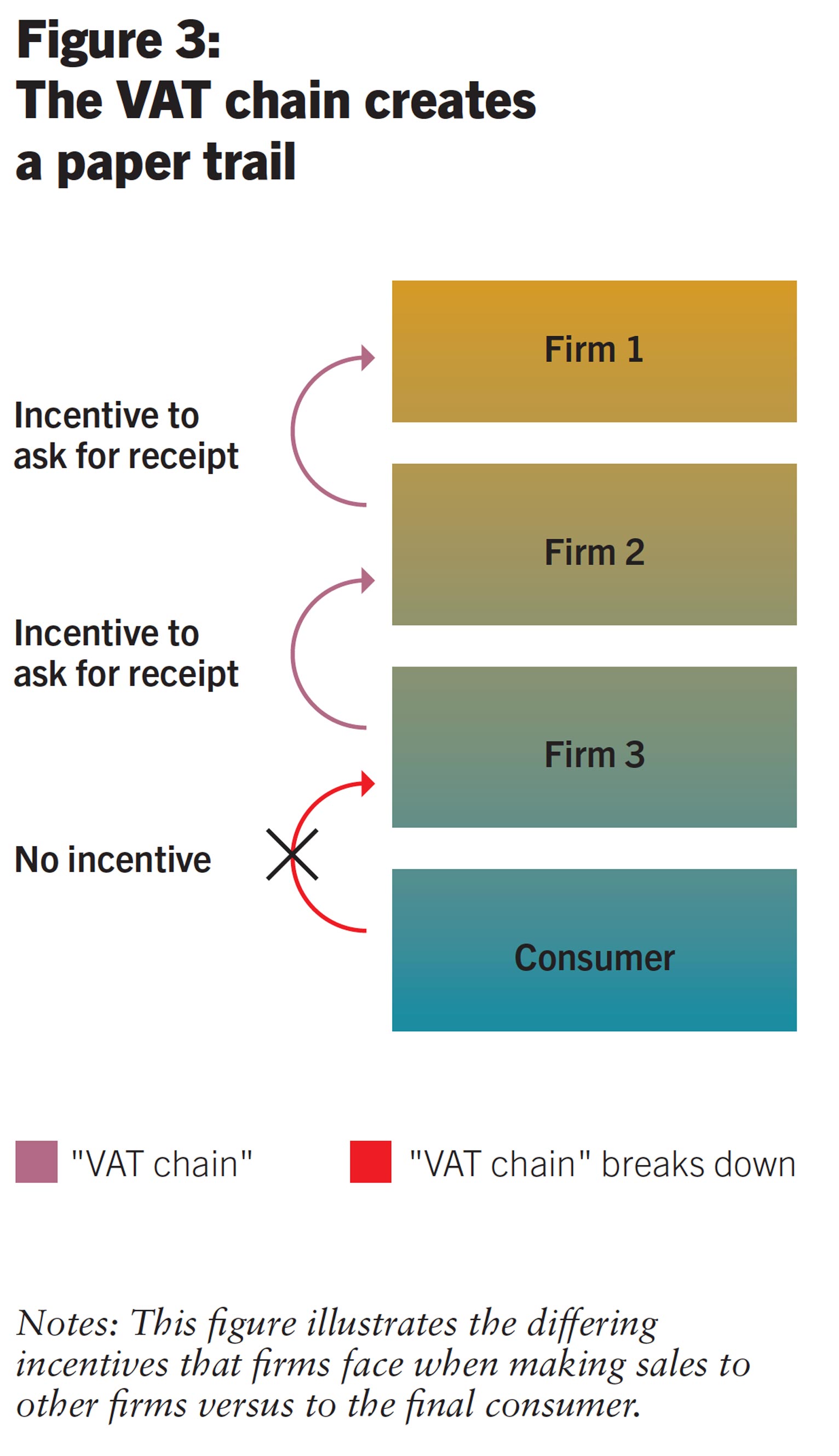

The VAT is paid by firms on the valueadded portion of their sales, i.e. on sales minus input costs. It had long been thought to have a “self-enforcing” property by providing downstream client firms with an incentive to ask suppliers for a receipt, which they can use to deduct the input costs from the VAT. This creates an auditable paper trail along the production chain (Figure 3). Due in part to the claimed selfenforcing property of VAT, the number of countries that adopted a VAT has increased from 50 in 1990 to over 165 today (OECD, 2016).

Yet rigorous evidence on the effectiveness of such a paper trail was scarce until recently. In many countries, firms often do not report information about their suppliers to the tax authority, and final consumers of a finished product or service do not have the same incentive to request receipts as firms do. These limitations may challenge the self-enforcement mechanism of VAT.

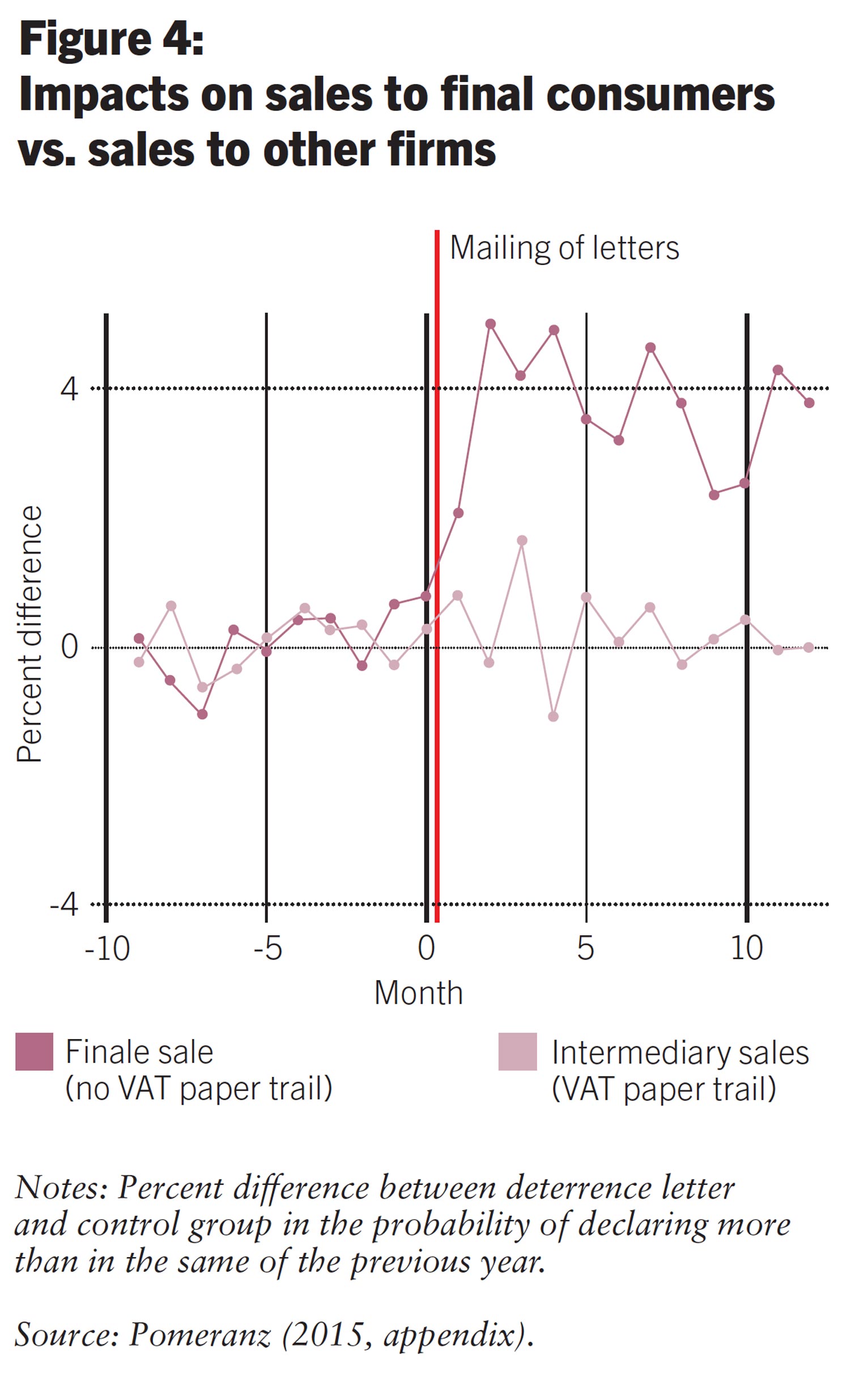

To examine this empirically, we partnered with the Chilean Tax Authority and sent letters to over 100,000 randomly selected firms, informing them that they had been randomly selected for special scrutiny and might be audited. We then analyzed whether the paper trail can act as a substitute for the audit probability by measuring whether increased tax enforcement had less impact where the paper trail was present. This was indeed the case: while the reported sales to final consumers increased sharply, firms did not noticeably change reported sales to other firms or input costs (Figure 4). In other words, a message announcing increased tax monitoring through audits had a much smaller effect on the reporting of transactions that were already covered by a paper trail.

We carried out a second experiment to observe the self-enforcement mechanism in action. In this experiment, we tested whether increasing enforcement on one firm leads to spillovers up the VAT chain. To do this, the tax authority selected 5,600 small firms suspected of tax evasion to be audited. Half of them were randomly selected to receive a pre-announcement of an upcoming audit, while the other half did not receive any advance notice.

In line with the prediction of the “selfenforcing” mechanism in the VAT, the audit announcement not only increased tax payments of the firms receiving the audit pre-announcement, but also of their suppliers. This suggests that firms expecting audits began demanding receipts from their suppliers as proof of their input costs. The demand for receipts created a paper trail documenting the sales of suppliers, forcing them to increase their VAT payments to avoid punishment for tax evasion.

Benefits of a verifiable paper trail

These findings suggest that verifiable paper trails can be a powerful tool for tax enforcement. Taxes such as the VAT may provide an advantage over other forms of taxation, such as a retail sales tax, because of the stronger paper trail. However, the results also show that information must be combined with deterrence to achieve effective tax enforcement.

The mere existence of the paper trail created by a VAT system does not incentivize firms toaccurately declare tax liabilities if the risk of being audited is low. The firms in the second experiment had low compliance before announcing audits; heightening deterrence by preannouncing audits was necessary to trigger the effectiveness of the VAT paper trail and increase tax payments by supplier firms.

VAT may encourage firms along the entire production chain to become part of the formal economy. Where VAT is present, formal firms tend to trade with other formal firms, since the latter can provide them with receipts that allow them to deduct their input costs from VAT payments. At the same time, informal firms tend to trade among themselves. Enforcing formalization at the final stage of production might contribute to formalizing entire production chains.

Forms of taxation that generate more information for the tax authority may have potential for improving tax collection. Other mechanisms, such as online billing systems or electronic receipts, may have high returns.

Ecuador: limitations of third-party reporting

The finding from Chile – that it was the combination of information with effective enforcement capacity that led to tax compliance – proved to be critical in a follow-up study that we undertook in collaboration with the tax authority in Ecuador (SRI), joint with Paul Carrillo and Monica Singhal. Ecuador had recently acquired the capability to electronically cross-check third-party information on a large scale. This allowed us to study the impact of the introduction of large-scale tax enforcement based on information cross-checks, and the challenges involved in such a policy reform.

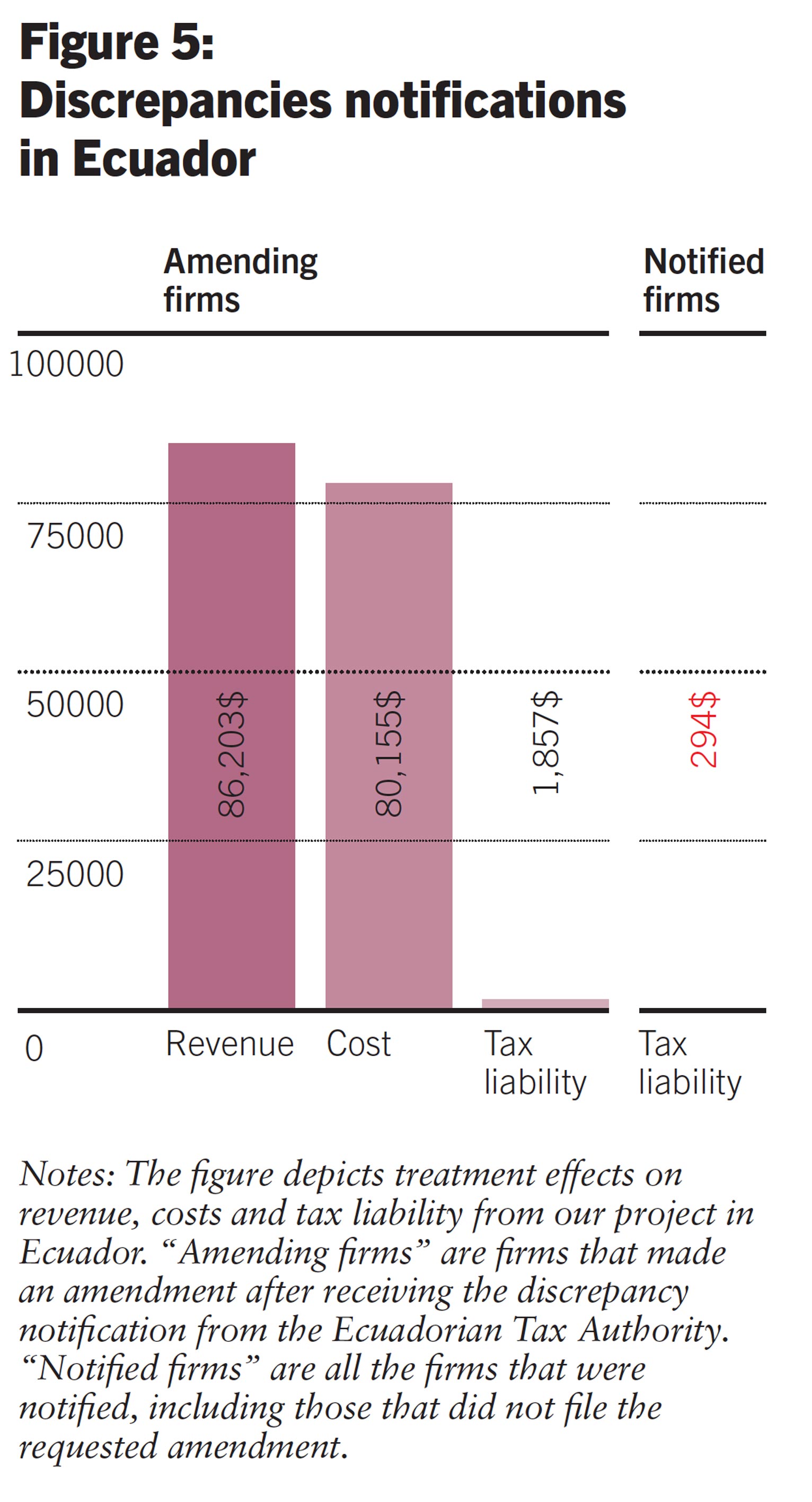

Using VAT data, as well as other sources such as credit card sales, the Ecuadorian tax authority developed estimates of a firm's revenues based on third-party information. Almost 8,000 firms were notified about large discrepancies detected between the sales they had reported and third-party estimates. The tax authority hoped that this would lead to a large increase in tax collection. However, the impact was below expectation, along two dimensions.

First, a large share of firms did not respond to the message. They anticipated – correctly – that the government did not have the capacity to formally audit and process the legal enforcement on so many firms in a short period of time. When overall compliance is low, firms can rationally assume that government cannot prosecute everyone.

Second, among the firms that did respond and increased their reported revenues, there was a large compensating reaction: they also increased their reported costs by a similar amount, leading to only small increases in tax payments (Figure 5). When third-party reporting is available on one margin of the tax declaration but not on others (in this example costs), the effectiveness of third-party reporting for tax enforcement can be severely limited. This concern can be an argument in favor of forms of taxation that provide thirdparty information covering the full tax base, as in the case of the turnover tax, as suggested by Best et al. (2015).

Strengthening state capacity and the ability to effectively and fairly collect taxes is a key priority for many governments around the world. Modern states execute a broad range of roles, ranging from assuring security, rule of law, and building infrastructure to providing services in the areas of education and health, or social programs. To be able to effectively implement these policies, countries need to acquire the ability to enforce compliance with tax obligations.

Low tax collection a century ago was not merely a political choice. Countries simply lacked the capacity for tax collection (e.g. Kleven et al. 2016). Throughout the twentieth century, most richer countries acquired a much higher tax collection capacity, and most high-income countries today have tax/GDP ratios between 25% an 50%. But countries with lower income per capita tend to have lower tax capacity and a smaller tax/GDP ratio (Figure 1). Combining a low GDP with less taxes collected as a share of GDP means the tax revenues are much lower than those in rich countries. In some countries, tax collection is smaller than international aid, and in low-income countries on average these two types of government revenue are of similar magnitude. In contrast, in middle-income countries, tax revenues are on average over 50 times larger than official development assistance (ODA), as shown in Figure 2. Raising tax collection capacity also allows countries to reduce their dependence on international aid.

Further reading

Allingham, Michael, and Agnar Sandmo (1972) ‘Income Tax Evasion: A Theoretical Analysis’, Journal of Public Economics 1(3-4): 323-38.

Besley, Timothy, and Torsten Persson (2013) ‘Taxation and Development’, in Handbook of Public Economics, Volume 5 edited by Alan Auerbach, Raj Chetty, Martin Feldstein and Emmanuel Saez, North-Holland.

Best, Michael Carlos, Anne Brockmeyer, Henrik Jacobsen Kleven, Johannes Spinnewijn, Mazhar Waseem (2015) ‘Production versus Revenue Efficiency with Limited Tax Capacity: Theory and Evidence from Pakistan.’, Journal of Political Economy 123 (6): 1311-1355.

Gordon, Roger, and Wei Li (2009) ‘Tax Structures in Developing Countries: Many Puzzles and a Possible Explanation.’, Journal of Public Economics 93 (7-8): 855-866

Kleven, Henrik, Martin Knudsen, Claus Kreiner, Søren Pedersen and Emmanuel Saez (2011) ‘Unwilling or Unable to Cheat? Evidence from a Tax Audit Experiment in Denmark’, Econometrica 79(3): 651-92.

Kopczuk, Wojciech, and Joel Slemrod (2006) ‘Putting Firms into Optimal Tax Theory.’, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 96 (2): 130-134

Naritomi, Joana (2016) ‘Consumers as Tax Auditors’, Working Paper.

OECD (2016) ‘Consumption Tax Trends 2016: VAT/GST and Excise Rates, Trends and Policy Issues.’, Paris: OECD Publishing.

Skinner, Jonathan, and Joel Slemrod (1985) ‘An Economic Perspective on Tax Evasion’, National Tax Journal 38(3): 345-53.

Author

Dina Pomeranz received her PhD from Harvard in 2010. Prior to joining the University of Zurich, she was an assistant professor at Harvard Business School and a Post-Doctoral Fellow at MIT's Poverty Action Lab. Her research focuses on developing countries, in particular on public finance, taxation, public procurement and firm development. Taking state-capacity research to the field, she works closely with the governments in Chile, Ecuador and Kenya to analyze strategies to strengthen public finance capabilities, and measure the impacts on government agencies, citizens and firms. Her work has been published in academic journals including the American Economic Review, the American Economic Journal - Applied Economics, and the Journal of Economic Development. In 2017, she was awarded one of the highly competitive ERC Starting Grants for her research on tax evasion and the role of firm networks. In 2018, she received the Excellence Prize in Applied Development Research of the “Verein für Socialpolitik”, was named as one of the top 10 most influential economists in Switzerland by a consortium of Swiss newspapers and was elected to the Council of the European Economic Association for a 5-year term.

Dina Pomeranz received her PhD from Harvard in 2010. Prior to joining the University of Zurich, she was an assistant professor at Harvard Business School and a Post-Doctoral Fellow at MIT's Poverty Action Lab. Her research focuses on developing countries, in particular on public finance, taxation, public procurement and firm development. Taking state-capacity research to the field, she works closely with the governments in Chile, Ecuador and Kenya to analyze strategies to strengthen public finance capabilities, and measure the impacts on government agencies, citizens and firms. Her work has been published in academic journals including the American Economic Review, the American Economic Journal - Applied Economics, and the Journal of Economic Development. In 2017, she was awarded one of the highly competitive ERC Starting Grants for her research on tax evasion and the role of firm networks. In 2018, she received the Excellence Prize in Applied Development Research of the “Verein für Socialpolitik”, was named as one of the top 10 most influential economists in Switzerland by a consortium of Swiss newspapers and was elected to the Council of the European Economic Association for a 5-year term.