2

Video summary

In a nutshell

A bad harvest can have severe consequences for farmers, especially in developing countries. But despite the significant advantages of agricultural insurance as a way to alleviate this risk, only a small percentage of farmers insure their crops. This policy brief outlines a simple but effective solution identified and tested by development economists, which has increased the adoption of crop insurance to over 70% of sugarcane farmers in Kenya. The key lies in shifting the time at which payment of premiums is required: from before the crop is harvested to afterwards.

A bad harvest can have severe consequences for farmers, especially in developing countries. But despite the significant advantages of agricultural insurance as a way to alleviate this risk, only a small percentage of farmers insure their crops. This policy brief outlines a simple but effective solution identified and tested by development economists, which has increased the adoption of crop insurance to over 70% of sugarcane farmers in Kenya. The key lies in shifting the time at which payment of premiums is required: from before the crop is harvested to afterwards.

Opportunities for action

1

Farmers are much more likely to buy crop insurance when payment of the premiums are delayed until after the harvest; demand increases most among the poorest farmers.

2

Key reasons why farmers may not buy insurance are that they are typically cash-constrained at planting time, and that they care more about the cost of insurance today than the potential protection from income losses from future crop failure.

3

Given considerable evidence that poor people don’t buy other types of insurance, including health insurance, understanding how to improve the timing of premium payment for these products is an important policy question.

1

Farmers are much more likely to buy crop insurance when payment of the premiums are delayed until after the harvest; demand increases most among the poorest farmers.

2

Key reasons why farmers may not buy insurance are that they are typically cash-constrained at planting time, and that they care more about the cost of insurance today than the potential protection from income losses from future crop failure.

Press

Kleiner Trick, grosse Wirkung: wie man armen Bauern zu mehr Sicherheit verhelfen kann NZZ vom 5.7.2019 lesen

Conclusions

Taken together, these results suggest that farmers are more willing to purchase insurance when they are able to pay the premium after the harvest. There are two likely reasons that timing affects this decision: farmers have limited cash before the harvest; and they are more likely to care about the costs of the premium today than about the potential costs from a crop failure in the future.

The results show that farmers do have high demand for insurance, but they have a low willingness to pay for it upfront. An important implication is that the low demand for standard insurance found in previous research should not be considered as evidence that farmers do not value riskmanagement products. Rather, other constraints – such as liquidity constraints – prevent them from taking full advantage of these products.

Given this simple and effective solution for a big problem, why is the idea not yet used extensively in the industry? One possible explanation is that insurers take an extra risk by allowing farmers to delay the premium payment. There is the risk that farmers will default when the time comes to pay, so it is important to increase the likelihood that they will indeed pay when the time comes.

For our experiment, we used a collection method that relied on our contract farming setting: tying the insurance contract to a sales contract. It is important to test how to enforce premium payment at harvest in other settings. For example, methods used in microfinance – such as relational contracting, group liability, and collateral – may be viable options.

This UBS Center Policy Brief summarizes ‘Time vs. State in Insurance: Experimental Evidence from Contract Farming in Kenya’ by Lorenzo Casaburi (University of Zurich) and Jack Willis (Columbia University), published in the American Economic Review 108(12): 3778-3813 in 2018.

Taken together, these results suggest that farmers are more willing to purchase insurance when they are able to pay the premium after the harvest. There are two likely reasons that timing affects this decision: farmers have limited cash before the harvest; and they are more likely to care about the costs of the premium today than about the potential costs from a crop failure in the future.

The results show that farmers do have high demand for insurance, but they have a low willingness to pay for it upfront. An important implication is that the low demand for standard insurance found in previous research should not be considered as evidence that farmers do not value riskmanagement products. Rather, other constraints – such as liquidity constraints – prevent them from taking full advantage of these products.

Callouts

In detail

Farming is risky: drought, flooding, pests, a bad harvest or a dip in crop prices can leave small farmers in developing countries without a steady income throughout the year. Attempts to mitigate these risks with agricultural insurance have typically been unsuccessful because farmers have chosen not to buy it (Cole and Xiong, 2017).

For decades, companies, aid organizations, and governments in developing countries have tried to increase the numbers of farmers who insure their crops. Yet demand for crop insurance has remained persistently low in spite of heavy subsidies, product innovation, and marketing campaigns.

In part, this low demand may be due to payment timing: most insurers offer insurance (and require premium payments) at planting time, when farmers are typically cash-constrained due to purchases of seeds and other materials.

Another reason that farmers may not purchase insurance is impatience: they might care more about the cost of insurance today than about the income they might lose due to a future crop failure.

Finally, farmers may not purchase insurance because they are not convinced that the insurer will actually pay them if their crops fail.

We partnered with a large sugarcane company in Kenya to run a ‘randomized controlled trial’, in which farmers were offered a different type of insurance product for which they can subscribe at planting time but only have to pay the premium at harvest time. This twist in the product design may address some of the reasons for low takeup of insurance – and indeed we find that farmers are much more likely to purchase insurance when the payments are delayed until after the harvest.

Textbook insurance

In the textbook model, insurance helps to transfer income across states of the world: from desirable states (such as a good harvest) to undesirable states (such as a bad harvest). In practice, however, most insurance products also transfer income across time: the premium is paid upfront with certainty, and any payouts are made in the future in the event of a bad state of the world.

As a result, the demand for insurance depends not just on risk aversion, but also on several additional factors, including:

Liquidity constraints: do buyers have the money to pay the premium now?

Intertemporal preferences: do buyers worry more about current costs than potential future costs?

Trust: do farmers believe that they will be paid in the event of a claim?

Since these factors can also make it harder to smooth consumption over time and hence to self-insure, charging the premium upfront may reduce demand for insurance precisely when the potential gains are largest – for example, among the poor.

Our study provides experimental evidence on the consequences of the transfer across time, common in insurance, by evaluating a crop insurance product that eliminates it.

Agriculture in Kenya

In sub-Saharan Africa, the majority of the working population works in agriculture, and small-scale farmers account for the vast majority of agricultural production. Sugarcane is one of the main cash crops in Kenya’s western region, where our evaluation took place.

Sugarcane farmers are typically poor. Nevertheless, sugarcane is a cash crop and thus these farmers are typically better off than those who grow crops merely for subsistence purposes. Crop production is subject to significant risks from rainfall, climate, pests, and fire. Very few farmers in the region have experience with formal insurance.

We partnered with a Kenyan sugar company, which uses a contract farming model to recruit farmers. In contract farming, a farmer signs an agreement to sell his crops to the company at harvest time and the buyer commits to purchase the crop.

At the start of planting season, companies typically offer farmers inputs such as seeds and fertilizer on credit, repayable in the future as a deduction from harvest revenue. This payment schedule can also be used for insurance: in the study setting, the sugar company could offer insurance at planting time with the premium payment deducted from harvest revenue.

The experimental intervention

Crop insurance usually has to be paid at the beginning of the season, just when the farmers need money for inputs, seeds, and machinery, and to feed their family until harvest, when they can sell their produce. In partnership with the sugar company, we offered farmers crop insurance with the premium due after the harvest to evaluate whether later payment would increase demand for the insurance.

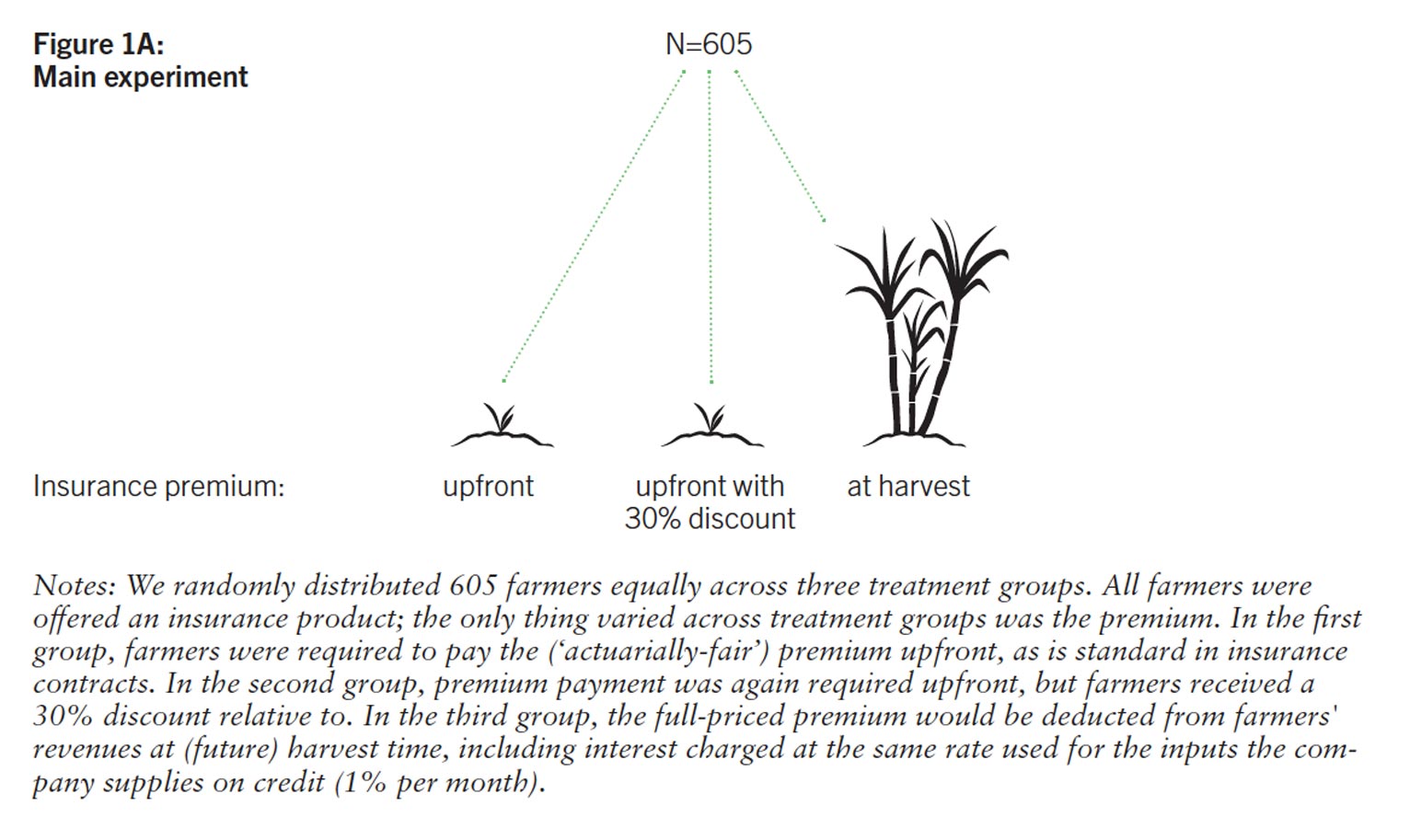

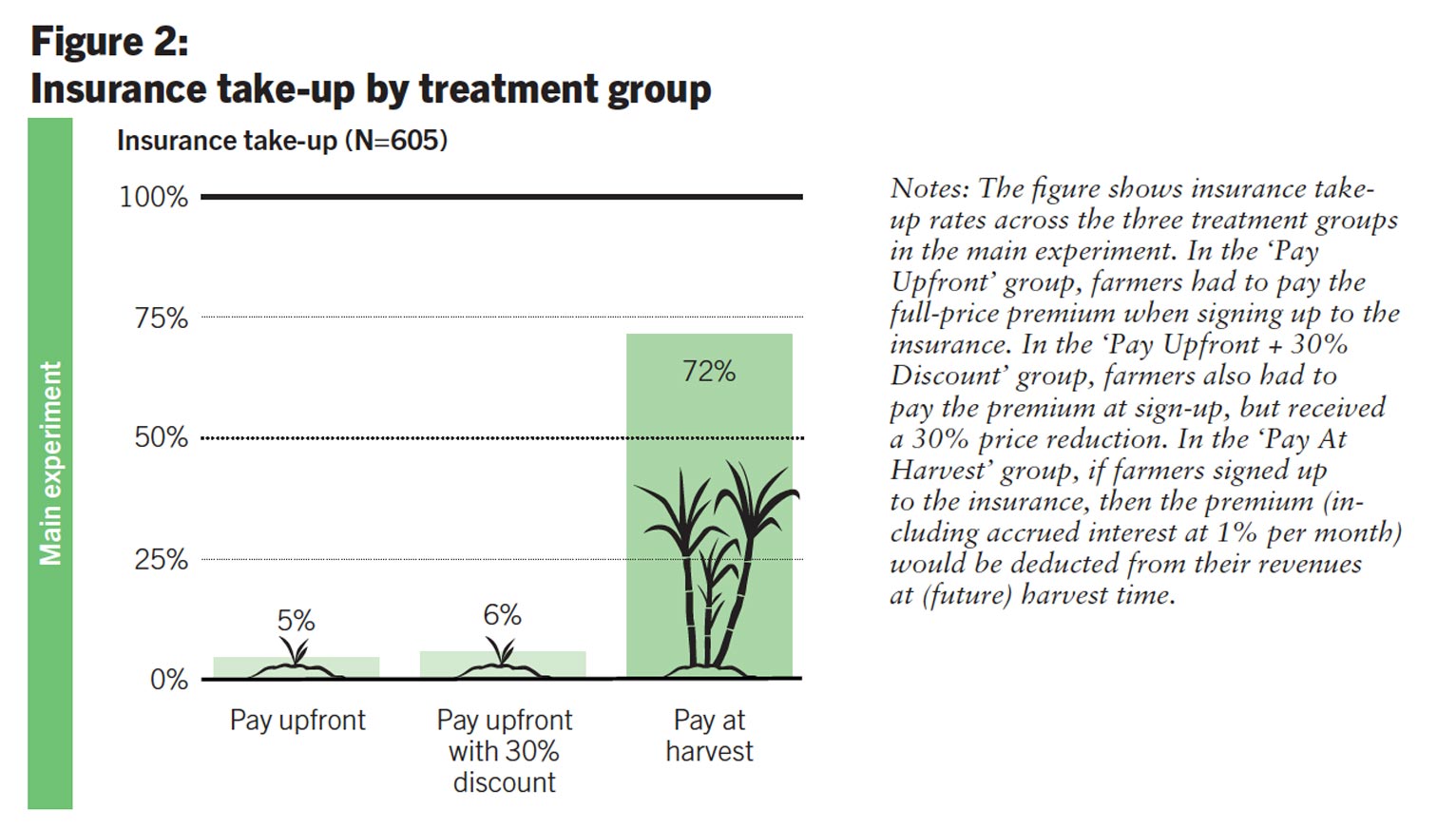

In our main experiment, we randomly assigned a sample of 605 sugarcane farmers to one of three groups (see Figure 1A):

Standard offer: Farmers were offered insurance at the market rate and had to pay the premium at planting time.

Discounted standard offer: Farmers were offered insurance with a 30% discount at planting time.

Harvest deduction offer: Farmers were offered insurance at the market rate, but the premium cost was deducted from their revenues at harvest time.

The sugar company offered identical insurance products across all three groups. If an insured farmer’s plot and neighboring farmers’ plots produced substantially less than a historical benchmark, the sugar company would distribute a payout covering up to 20% of the farmer’s predicted revenues.

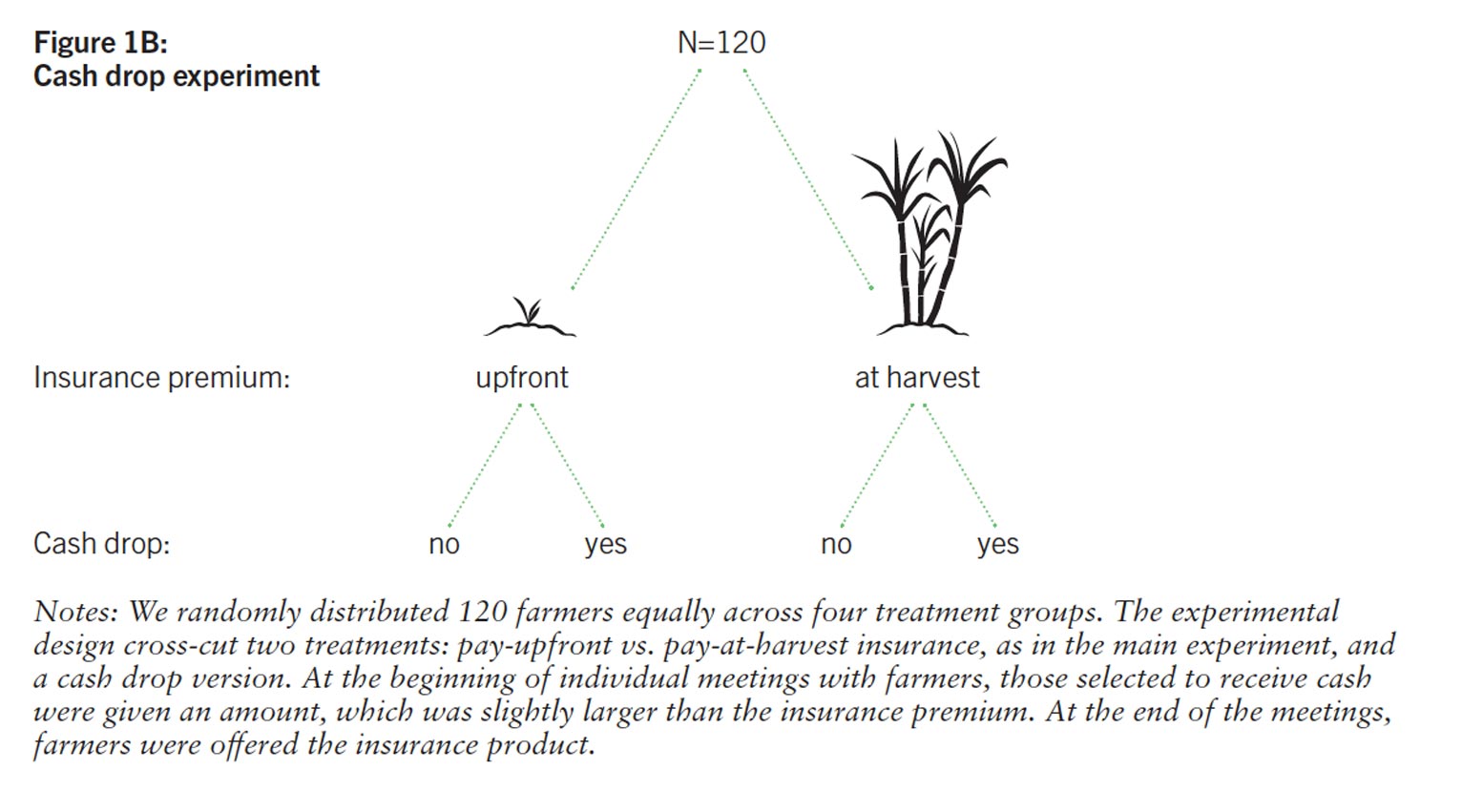

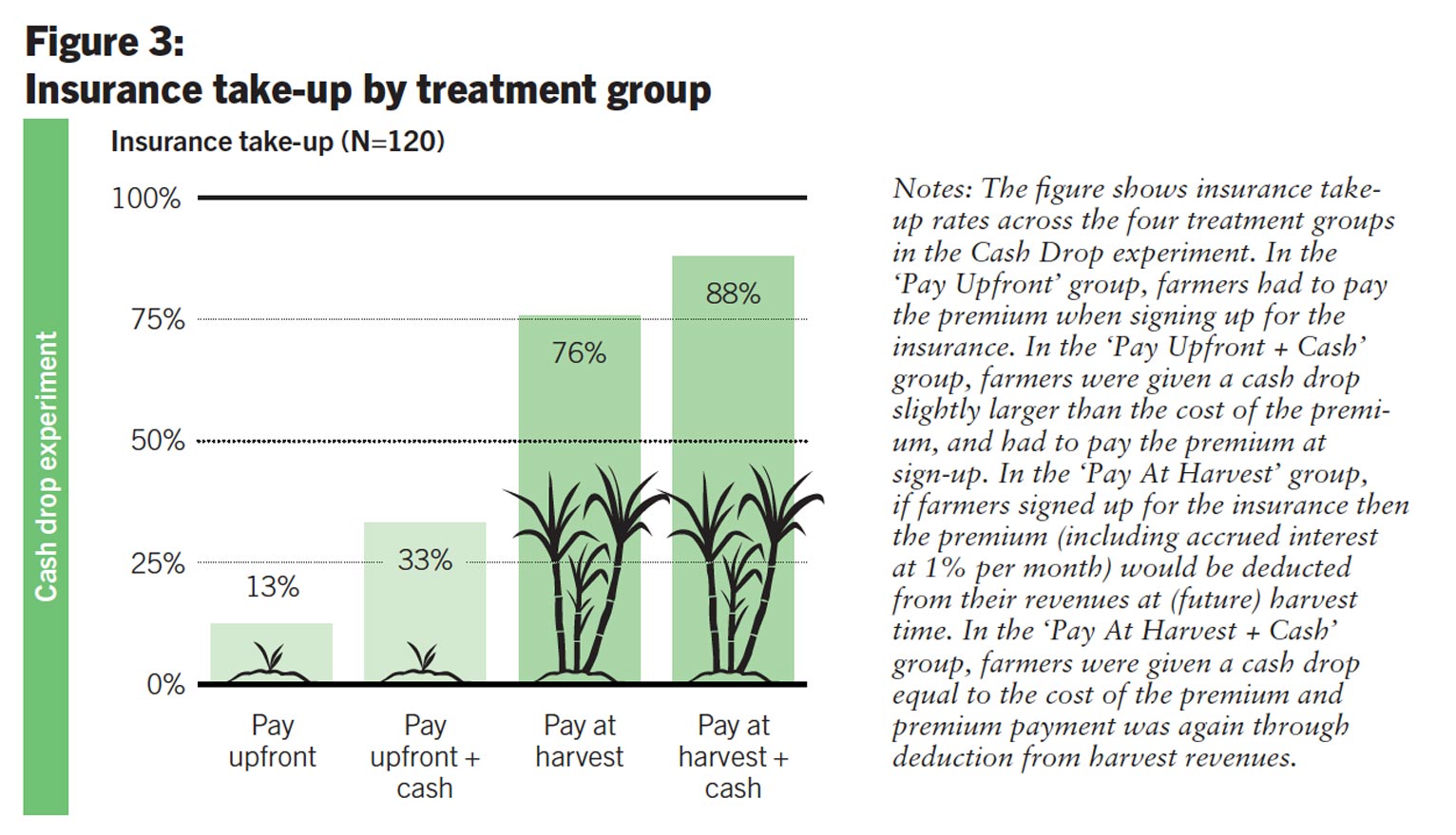

We complemented these offers with two smaller experiments to understand why delaying premium payments might increase demand for insurance. In our ‘cash drop’ experiment (see Figure 1B), we gave 120 randomly selected farmers an amount of cash that was slightly more than the insurance premium cost, ensuring that these farmers could purchase insurance if they wanted it.

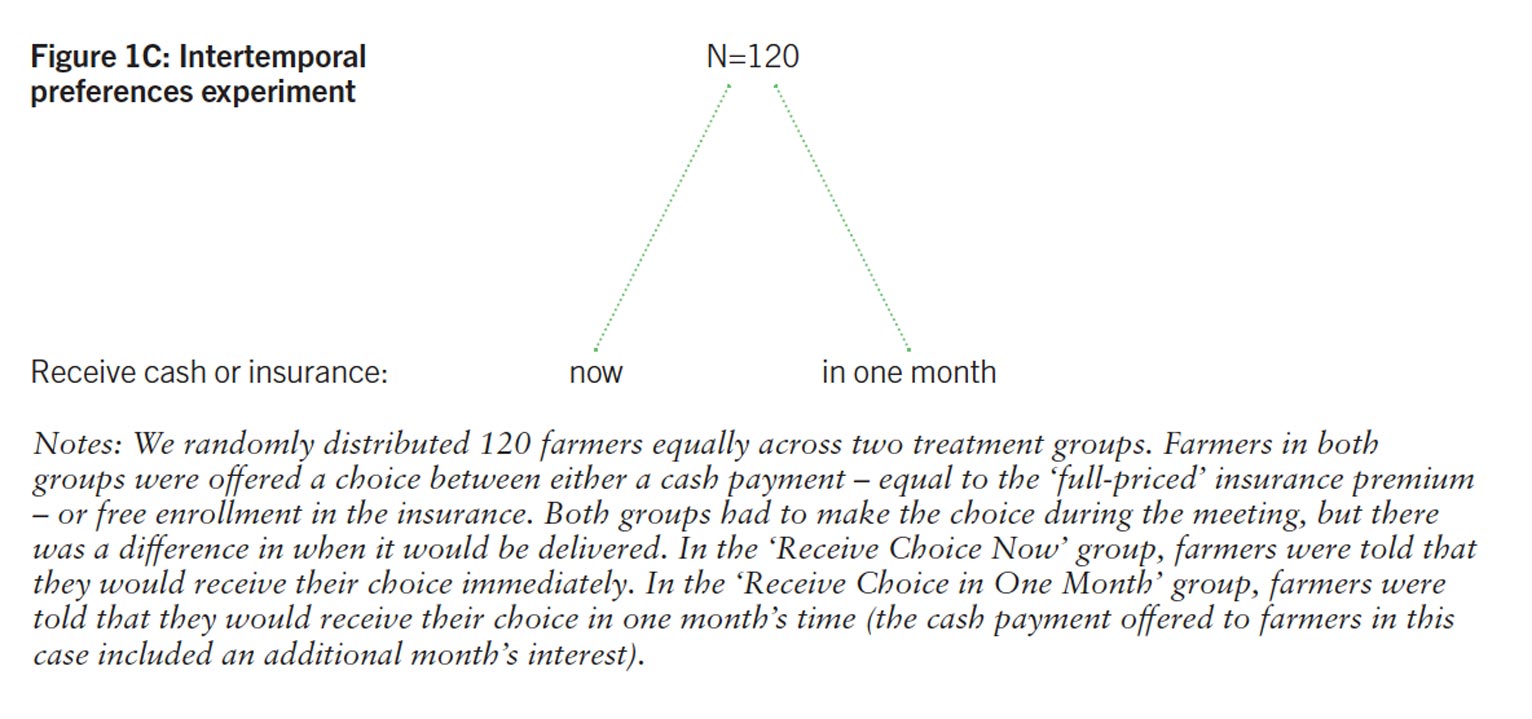

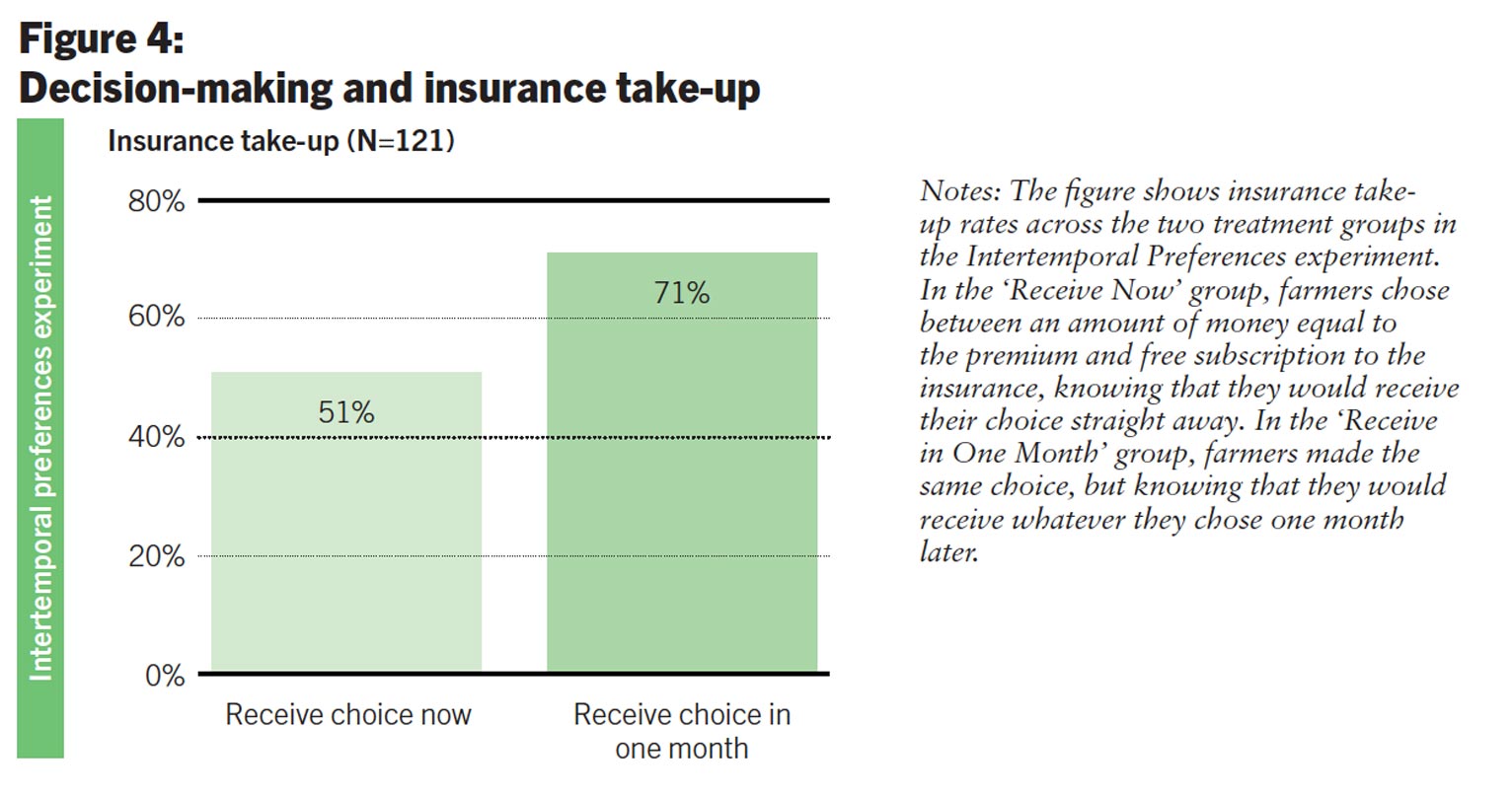

In our ‘intertemporal preferences’ experiment (see Figure 1C), we offered another 120 randomly selected farmers the choice between a cash grant equal to the insurance premium or free insurance. This enabled us to test whether demand to pay upfront is low because the premium must be paid immediately at sign-up and farmers put a very high weight on immediate costs – a kind of behavior known as ‘present bias’ (see Ericson and Laibson, 2019). A randomly assigned half of these farmers were told that they would receive their choice immediately, while the other half were told that they would receive their choice in one month. If farmers did suffer from present bias, then delaying the choice could help overcome their tendencies to care more about income in the present than potential losses in the future.

Results

Overall, we find that farmers are much more likely to purchase insurance when they do not have to make payments until after the harvest. We also find that demand for the standard insurance offer is likely to be low for three reasons: farmers may have limited cash to purchase insurance before the harvest; they may suffer from present bias; and they may not trust insurers to follow through on their payments if a crop failure occurs.

Only 5% of farmers who were offered standard insurance decided to purchase it. Offering a discount on stan dard insurance did not increase farmers’ demand for it. However, 72% of those offered the harvest deduction insurance purchased it (see Figure 2). In addition, this increase in uptake is larger for poorer farmers, who may face more severe liquidity constraints.

Giving cash grants to farmers increases their purchases of the standard insurance, but to a much lesser extent than offering harvest deduction insurance (see Figure 3). When the payment is delayed by a month, farmers are more likely to choose insurance over cash, suggesting that they may suffer from present bias (see Figure 4).

Finally, because of financial problems, the sugar company had to delay harvesting for many farmers, inducing them to sell to other buyers. This shows the importance of trust: farmers must believe the insurer will pay the insurance. Delaying the premium payment until harvest time saves farmers the premium if the insurer defaults before harvest.

Farming is risky: drought, flooding, pests, a bad harvest or a dip in crop prices can leave small farmers in developing countries without a steady income throughout the year. Attempts to mitigate these risks with agricultural insurance have typically been unsuccessful because farmers have chosen not to buy it (Cole and Xiong, 2017).

For decades, companies, aid organizations, and governments in developing countries have tried to increase the numbers of farmers who insure their crops. Yet demand for crop insurance has remained persistently low in spite of heavy subsidies, product innovation, and marketing campaigns.

Further reading

Cole, Shawn, and Wentao Xiong (2017) ‘Agricultural Insurance and Economic Development’, Annual Review of Economics 9: 235-62.

Ericson, Keith Marzilli, and David Laibson (2019) ‘Intertemporal Choice’, Chapter 1 in Handbook of Behavioral Economics – Foundations and Applications 2, Volume 2 edited by Douglas Bernheim, Stefano Della Vigna, and David Laibson, Elsevier.

Author

Lorenzo Casaburi is UBS Foundation Associate Professor of Development Economics at the Department of Economics, University of Zurich. His main line of research focuses on agricultural markets in Sub-Saharan Africa, with an emphasis on market structure, behavioral insights, and agricultural finance. He also works on state capacity, with an emphasis on tax enforcement and redistribution policies. For his research, he has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant), the Swiss National Foundation (Eccellenza Grant), USAID, and DFID, among others. Lorenzo holds a B.A. from the University of Bologna and a Ph.D. in Economics from Harvard. Before joining Zurich, he was a postdoc at Stanford SIEPR. He is a Research Fellow at CEPR and a Research Affiliate at BREAD, IGC, IPA, and J-PAL.

Lorenzo Casaburi is UBS Foundation Associate Professor of Development Economics at the Department of Economics, University of Zurich. His main line of research focuses on agricultural markets in Sub-Saharan Africa, with an emphasis on market structure, behavioral insights, and agricultural finance. He also works on state capacity, with an emphasis on tax enforcement and redistribution policies. For his research, he has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant), the Swiss National Foundation (Eccellenza Grant), USAID, and DFID, among others. Lorenzo holds a B.A. from the University of Bologna and a Ph.D. in Economics from Harvard. Before joining Zurich, he was a postdoc at Stanford SIEPR. He is a Research Fellow at CEPR and a Research Affiliate at BREAD, IGC, IPA, and J-PAL.