Innovation-driven economic growth

Last year's Nobel Prize winners in economics demonstrate how sustained economic growth is possible using methods from history and economics. Whether economic growth continues or not will also depend on politics.

This article by Timo Boppart and David Hémous was originally published in 'Die Volkswirtschaft' on 25.11.2025 in German. Translated and edited for context purposes by the UBS Center.

For most of history, humans have experienced economic stagnation. Income per capita in the Roman empire was almost the same as in Western Europe in the 1600s. And even when living standards in England gradually improved, it was a slow process: although income per capita rose by two-thirds between 1300 and 1700, this corresponded to an annual growth rate of only 0.13 percent.

As described by British economist Thomas Malthus in 1798, any burst of technological progress was undone by growing populations, and living standards returned to subsistence. Then the Industrial Revolution broke the trap. From roughly 1800 onward, income per capita began to rise at a sustained pace in Britain and, soon after, across much of the world.

Last year's Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences honors three scientists who have significantly advanced our understanding of sustained economic growth. Using different but complementary methods, economic historian Joel Mokyr and growth theorists Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt show how innovation-driven growth and the process of creative destruction have led economies out of stagnation and enabled sustained growth.

Theory and practice combined

Mokyr's work answers major historical questions: Why did the Industrial Revolution begin in the mid-18th century? Why did it begin in Europe, and specifically in Great Britain? And why did growth continue?

Mokyr argues that civilizations before 1800 often produced brilliant ideas or clever inventions, but were unable to translate these breakthroughs into progress. The Industrial Enlightenment strengthened the link between propositional knowledge (ideas about nature) and prescriptive knowledge (techniques and blueprints). This made it easier for experienced tinkerers—engineers and craftsmen—to put theory into practice.

Crucially, Britain combined this knowledge ecosystem with a political climate that was more tolerant of “creative destruction” and allowed new technologies to spread even when incumbents resisted them. Institutions such as the British Parliament played a role here, as they facilitated compromise. The result was not just a takeoff, but a takeoff that did not stall.

Creative destruction modeled

The term “creative destruction” is closely associated with the work of Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950). He argued that growth results from dynamic competition between entrepreneurs who are constantly introducing new products and processes. The new replaces the old, thereby shifting market shares and profits.

Aghion and Howitt, the two other Nobel Prize winners alongside Mokyr, formalized Schumpeter's idea in a modern mathematical macroeconomic model. In this model, innovators are motivated to improve the quality of existing products because of temporary monopoly profits. The profits are only temporary, as others can develop further innovations on this basis and take over market leadership. Aghion and Howitt use their model to explain how these constant upheavals of rising and failing companies can nevertheless lead to steady growth at the aggregate level – as developed economies have experienced since the mid-19th century.

Their work also shows that market imperfections and externalities cause the actual rate of innovation to deviate from the socially optimal rate. On the one hand, innovators build on the shoulders of giants: when companies introduce better products, they also enable their competitors to build on their innovations. This is a positive externality for which innovators are not paid and which could lead to too little innovation without policy interventions such as the promotion of research and development.

On the other hand, there are also negative externalities. Innovators are also motivated by the possibility of capturing the profits of incumbents. However, this “business stealing” effect does not lead to any social added value. Empirically, positive externalities outweigh negative ones at the aggregate level. However, in some sectors with frequent but marginal innovations, negative externalities may prevail.

Empirical evidence?

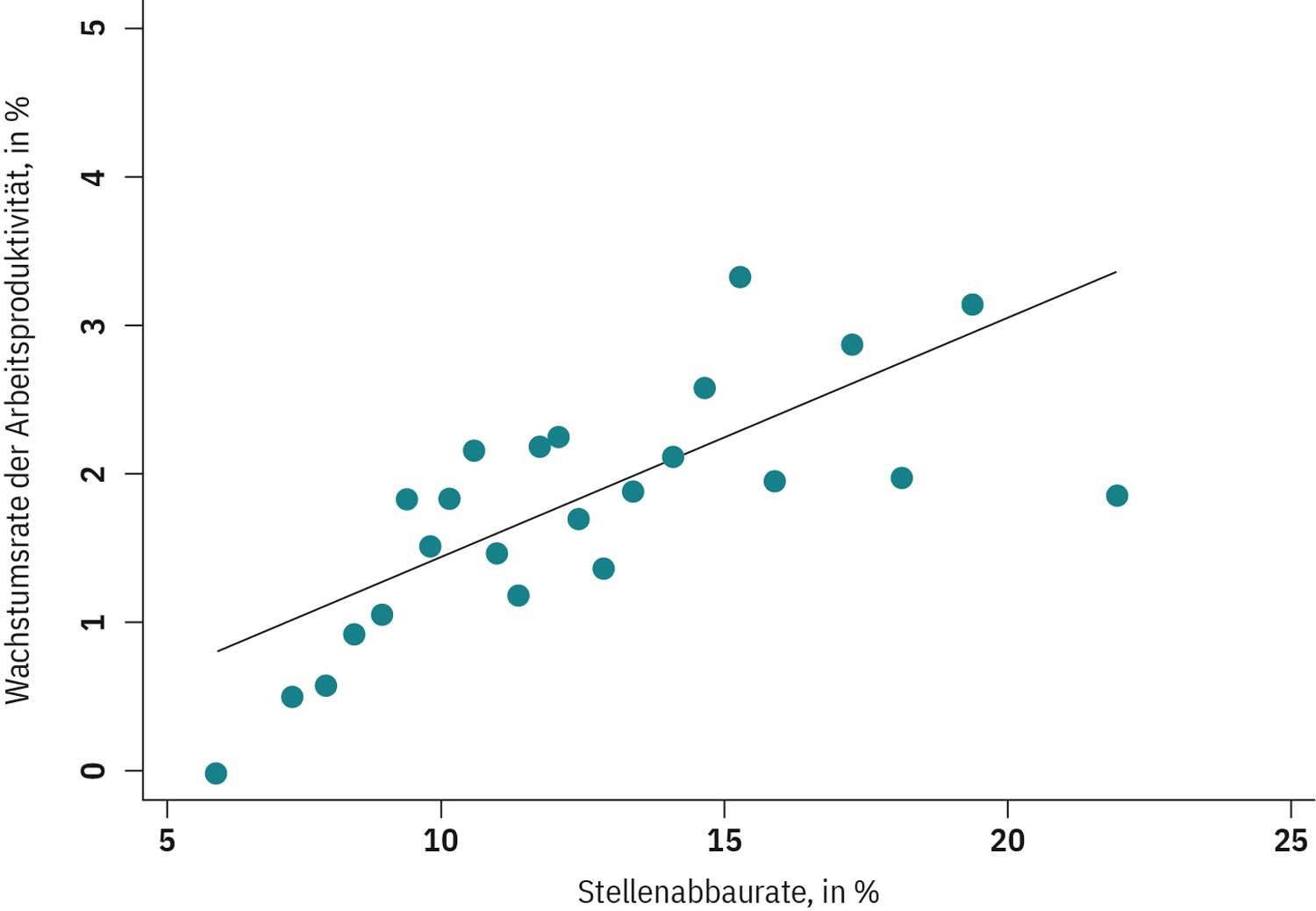

But what is the empirical evidence for this theoretical link between growth and churn? Several economists have measured this upheaval in specific sectors: How many jobs are created and destroyed in a year? How many companies are founded, and how many go under? Labor productivity growth correlates positively with these metrics between U.S. industries and over time (see figure). This means that industries and periods with greater business dynamism show faster growth—just as in Aghion and Howitt's model.

Politics can provide support

Since innovation creates winners and losers, incumbents often try to block market entry. And since innovation also generates profits, it generate inequalities. In both Mokyr's historical analysis and Aghion and Howitt's work, institutions and politics are therefore important levers for enabling change. For example, policymakers can distribute the returns from disruptive innovations more broadly, protect affected workers, and thus create support for change.

Today, Aghion and Howitt's approach has become the standard model in growth economics. By focusing on entrepreneurs and firms, their model paved the way for empirical work with microdata at the company level. Building on further work, economists today use firm-level data to quantify how much growth comes from market entrants versus incumbents and how much comes from improving existing products versus expanding into new product lines.

Current implications

The study of economic growth and innovation is highly topical: Are today's superstar companies so profitable because they are innovative or because they block innovation? The answer to this question has important policy implications. Another question is: How can we reconcile growth and environmental sustainability? Some answers to these pressing questions can be found in models based directly on the Aghion-Howitt model.

For example, last year's Nobel Prize winner Daron Acemoglu, together with Philippe Aghion, Leonardo Bursztyn, and David Hémous explains that due to the “standing on the shoulders of giants” externalities, a successful green transition requires an innovation policy specifically geared toward supporting green innovations. And a study by Philippe Aghion, Timo Boppart, and other researchers analyzes how qualitative and quantitative growth have become decoupled from each other, mitigating the environmental footprint of the growth process.

Aghion and Mokyr at the University of Zurich

Overall, the laureates have given us an understanding of what lies behind sustained economic growth and how policy can influence this process. This knowledge will be invaluable in tackling the challenges ahead and steering the growth process in a direction that brings the greatest benefit to humanity.

Philippe Aghion and Joel Mokyr are both frequent visitors to Zurich and members of the advisory board of the UBS Center at the Department of Economics at the University of Zurich. We have also had the good fortune to work with Philippe Aghion and share his enthusiasm for research. Philippe Aghion was David Hémous' doctoral supervisor, and we have both benefited enormously from his generous support over the years.

Last year's Nobel Prize winners in economics demonstrate how sustained economic growth is possible using methods from history and economics. Whether economic growth continues or not will also depend on politics.

This article by Timo Boppart and David Hémous was originally published in 'Die Volkswirtschaft' on 25.11.2025 in German. Translated and edited for context purposes by the UBS Center.

For most of history, humans have experienced economic stagnation. Income per capita in the Roman empire was almost the same as in Western Europe in the 1600s. And even when living standards in England gradually improved, it was a slow process: although income per capita rose by two-thirds between 1300 and 1700, this corresponded to an annual growth rate of only 0.13 percent.

Literature

Acemoglu, D., P. Aghion, L. Bursztyn, und D. Hémous (2012). The Environment and Directed Technical Change. American Economic Review, 102(1), pp. 131–166.

Aghion, P., T. Boppart, M. Peters, M. Schwartzman und F. Zilibotti (2025). A Theory of Endogenous Degrowth and Environmental Sustainability. No. w33634. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2025.

Aghion, P. und P. Howitt (1992). A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction. Econometrica 60(2), 323–351.

Broadberry, S., B. M. Campbell, A. Klein, M. Overton und B. Van Leeuwen (2015). British Economic Growth, 1270–1870. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, S. J. und J. Haltiwanger (1992). Gross Job Creation, Gross Job Destruction, and Employment Reallocation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107(3), 819–863.

Klette, T. und S. Kortum (2004). Innovating Firms and Aggregate Innovation. Journal of Political Economy 112(5), 986–1018.

UBS Center Opinions

Contact

Timo Boppart joined the UZH Department of Economics as Professor of Macroeconomics and Political Economy in 2024. Boppart’s research work focuses on the field of economic growth, firm dynamics, labor supply and development. Completing his doctorate in 2012 at the University of Zurich, he then moved to the Institute for International Economic Studies at Stockholm University, where he was an associate professor from 2019 - 2024. In 2020, he was also appointed full professor at the Swiss Institute for International Economics and Applied Economic Research at the University of St. Gallen. He has been a member of the prize committee for the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences since 2023.

David Hémous received his PhD from Harvard University in 2012. He is a macroeconomist working on economic growth, climate change and inequality. His work highlights that innovation responds to economic incentives and that public policies should be designed taking this dependence into account. In particular, he has shown in the context of climate change policy that innovations in the car industry respond to gas prices and that global and regional climate policies should support clean innovation to efficiently reduce CO2 emissions. His work on technological change and income distribution shows that higher labor costs lead to more automation, and that the recent increase in labor income inequality and in the capital share can be explained by a secular increase in automation. He has also shown that innovation affects top income shares. He was awarded an ERC Starting Grant on 'Automation and Income Distribution – a Quantitative Assessment' and he received the 2022 'European Award for Researchers in Environmental Economics under the Age of Forty'.

Timo Boppart joined the UZH Department of Economics as Professor of Macroeconomics and Political Economy in 2024. Boppart’s research work focuses on the field of economic growth, firm dynamics, labor supply and development. Completing his doctorate in 2012 at the University of Zurich, he then moved to the Institute for International Economic Studies at Stockholm University, where he was an associate professor from 2019 - 2024. In 2020, he was also appointed full professor at the Swiss Institute for International Economics and Applied Economic Research at the University of St. Gallen. He has been a member of the prize committee for the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences since 2023.

David Hémous received his PhD from Harvard University in 2012. He is a macroeconomist working on economic growth, climate change and inequality. His work highlights that innovation responds to economic incentives and that public policies should be designed taking this dependence into account. In particular, he has shown in the context of climate change policy that innovations in the car industry respond to gas prices and that global and regional climate policies should support clean innovation to efficiently reduce CO2 emissions. His work on technological change and income distribution shows that higher labor costs lead to more automation, and that the recent increase in labor income inequality and in the capital share can be explained by a secular increase in automation. He has also shown that innovation affects top income shares. He was awarded an ERC Starting Grant on 'Automation and Income Distribution – a Quantitative Assessment' and he received the 2022 'European Award for Researchers in Environmental Economics under the Age of Forty'.