The Zero Marginal Cost Society

Whether you call it the third or the fourth industrial revolution, we are entering an era of unprecedented economic, technological and social change. But what are the forces driving this change and will humanity benefit or suffer as a result?

by Maura Wyler

A matter of survival

Jeremy Rifkin kicked off this year’s Forum for Economic Dialogue with a tour de force taking the title from his best-selling book, The Zero Marginal Cost Society. The first and second industrial revolutions have taken us from a largely agrarian society to a highly sophisticated urban and industrialized world. But this progress has not eliminated poverty or inequality. In fact, the world’s 62 richest individuals now hold more wealth than half the world’s population, i.e. 3.5 billion people. The global fall in productivity and slowing growth of recent decades are inevitable consequences of the failure to extract further growth from aging technologies as they reach the physical limits of thermodynamic laws, argues Rifkin.

More ominously, climate change resulting from our continued dependence on first and second industrial revolution technologies and energy, in particular fossil fuels, threatens humanity with an existential crisis.

Smart technology, smart economy

In Rifkin’s vision of the future the traditional model of buying and selling goods, driven by industrial-age technology and energy, will be replaced by a digitalized Internet of Things. In this new economic model, products and goods are produced at zero marginal cost using 3-D printing and shared via a transport network of GPS-automated driverless vehicles, propelled by clean engines. This new economy will be fuelled by unlimited and renewable energy sources supplied by smart grids that are largely self-sustaining, producing limitless energy from clean sources, all at zero marginal cost.

The great challenge for the current and last generations of the industrial age will be to build the infrastructure of this new economy that will require the labor of millions over at least two generations. Businesses and banks will plan, build and finance the construction of this new global infrastructure. Once it’s completed, they will manage and maintain the infrastructure as service providers. IBM is one company that has already shifted from manufacturing and selling hardware to building and managing networks and services for clients, says Rifkin. Energy and technology giants like EON and ABB are also moving toward new business models based on the construction, management and optimization of smart-energy networks using renewable energy.

Whether you call it the third or the fourth industrial revolution, we are entering an era of unprecedented economic, technological and social change. But what are the forces driving this change and will humanity benefit or suffer as a result?

by Maura Wyler

A matter of survival

Jeremy Rifkin kicked off this year’s Forum for Economic Dialogue with a tour de force taking the title from his best-selling book, The Zero Marginal Cost Society. The first and second industrial revolutions have taken us from a largely agrarian society to a highly sophisticated urban and industrialized world. But this progress has not eliminated poverty or inequality. In fact, the world’s 62 richest individuals now hold more wealth than half the world’s population, i.e. 3.5 billion people. The global fall in productivity and slowing growth of recent decades are inevitable consequences of the failure to extract further growth from aging technologies as they reach the physical limits of thermodynamic laws, argues Rifkin.

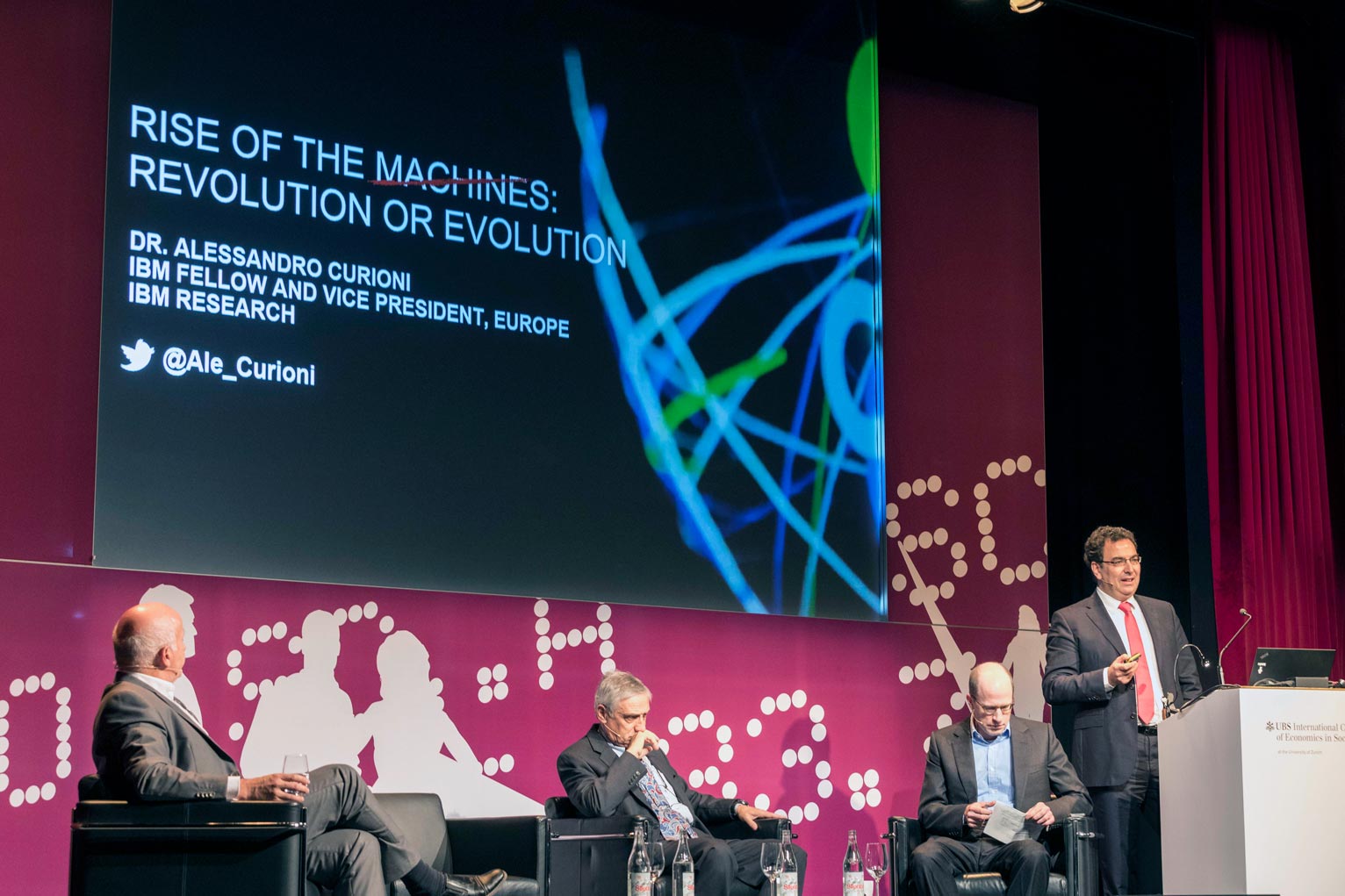

Revolution or evolution

Rifkin’s bold vision of a zero marginal cost digital future posed as many questions as it answered and was the subject of heated debate in the ensuing panel discussions. The first panel “The Rise of the Machines – Revolution or Evolution?” explored the age-old discussion of man vs. machine and concluded that it was unlikely machines would ever reach a level of human consciousness or intelligence. Machines will become indispensable aids to people in performing tasks of increasing complexity that demand an ever-greater capacity to manage, store, filter and interpret data. But these machines will still require humans to provide input and ask the questions that demand answers.

Rifkin’s bold vision of a zero marginal cost digital future posed as many questions as it answered and was the subject of heated debate in the ensuing panel discussions. The first panel “The Rise of the Machines – Revolution or Evolution?” explored the age-old discussion of man vs. machine and concluded that it was unlikely machines would ever reach a level of human consciousness or intelligence. Machines will become indispensable aids to people in performing tasks of increasing complexity that demand an ever-greater capacity to manage, store, filter and interpret data. But these machines will still require humans to provide input and ask the questions that demand answers.

Hey robot, where’s my job

The afternoon panel discussions revolved around the subject of how humans will adapt to a machine-driven economy and whether large segments of the workingage population would find themselves redundant and out of work. The afternoon session looked at “Policies for the Machine Age.” It concluded that government and business-led training programs will be urgently needed to fill the skills gap especially in information and communications technology (ICT) that will be essential to help millions transition to the machine age.

At the same time, closing borders and shutting out immigration to protect unqualified native workers would be counterproductive and most likely stall progress toward a digital future.

The final session was a disputation on “The Rise of Machines – Boon or Bane for Workers?” It noted the contradiction that each wave of technological progress, while destroying existing industries, always succeeded in creating many more new jobs in new ones. There are more jobs and more people in work in the US than ever before, but pointed out the irony that a transformative technology product like Apple’s iPhone could not be manufactured in the US for regulatory reasons.

The afternoon panel discussions revolved around the subject of how humans will adapt to a machine-driven economy and whether large segments of the workingage population would find themselves redundant and out of work. The afternoon session looked at “Policies for the Machine Age.” It concluded that government and business-led training programs will be urgently needed to fill the skills gap especially in information and communications technology (ICT) that will be essential to help millions transition to the machine age.

At the same time, closing borders and shutting out immigration to protect unqualified native workers would be counterproductive and most likely stall progress toward a digital future.

Why are there still so many jobs

David Autor from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) closed the day by addressing the contradiction that there are now more bank tellers in the US than ever before, despite the invention of the automatic cash dispenser (ATM) 40 years ago. Labor participation in the US and the developed world has risen steadily over the last 125 years. The US has added 14 million new jobs since 2010 alone. His explanation is that new technology always expands the possibilities and creates new ideas for products and services and these require people to develop, refine and sell them, which drives further consumption. Modern bank tellers don’t just dispense cash or hand out forms, but also provide advice and assistance to customers bewildered by the growing numbers of products and services available.

However, automation and technology is polarizing the workforce with growing numbers of poorly paid, low-skilled jobs on one side, and highly paid, highskilled work on the other, while middle income, medium-skilled work disappears. This creates major challenges not least in perpetuating inequality and poverty and restricting equality of opportunity. These are not problems that can be solved by the market, says Autor, but by governments and social institutions.

David Autor from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) closed the day by addressing the contradiction that there are now more bank tellers in the US than ever before, despite the invention of the automatic cash dispenser (ATM) 40 years ago. Labor participation in the US and the developed world has risen steadily over the last 125 years. The US has added 14 million new jobs since 2010 alone. His explanation is that new technology always expands the possibilities and creates new ideas for products and services and these require people to develop, refine and sell them, which drives further consumption. Modern bank tellers don’t just dispense cash or hand out forms, but also provide advice and assistance to customers bewildered by the growing numbers of products and services available.

However, automation and technology is polarizing the workforce with growing numbers of poorly paid, low-skilled jobs on one side, and highly paid, highskilled work on the other, while middle income, medium-skilled work disappears. This creates major challenges not least in perpetuating inequality and poverty and restricting equality of opportunity. These are not problems that can be solved by the market, says Autor, but by governments and social institutions.