9

Video summary

Challenges of a fair tax system

Over the past decades, many developed countries have experienced considerable increases in income and wealth inequality, led by an extraordinary concentration among the very richest swath of households. This has focused policy attention on the superrich. Various political and economic arguments for at least partially offsetting this rise in inequality have been put forward. In particular, politicians have called for increasing the tax burden on rich households, both in the form of higher top rates for existing income taxes as well as new tax levies targeting the superrich. Most prominently, the idea of introducing an annual wealth tax has recently gained attention in the United States.

This Public Paper provides an overview of the tax situation the superrich currently face and evaluates various reform proposals. We emphasize that the incomes of the superrich are qualitatively different from others. Some are “superstars,” for whom small differences in talent are magnified into much larger earnings differences, while others work in winner-take-all markets, meaning that their effort to climb the ladder of success reduces the returns to others. Moreover, the discussion about tax rates must be accompanied by attention to the tax base, with a special focus on capital gains, which comprise a large fraction of the taxable income of the superrich. We also review the pros and cons of wealth taxes versus alternative policies that achieve similar objectives. While a dozen OECD countries levied wealth taxes in the recent past, only three retain them at present. Only Switzerland raises a similar fraction of revenue with its wealth tax as the recent U.S. proposals, therefore serving as a useful example.

Over the past decades, many developed countries have experienced considerable increases in income and wealth inequality, led by an extraordinary concentration among the very richest swath of households. This has focused policy attention on the superrich. Various political and economic arguments for at least partially offsetting this rise in inequality have been put forward. In particular, politicians have called for increasing the tax burden on rich households, both in the form of higher top rates for existing income taxes as well as new tax levies targeting the superrich. Most prominently, the idea of introducing an annual wealth tax has recently gained attention in the United States.

This Public Paper provides an overview of the tax situation the superrich currently face and evaluates various reform proposals. We emphasize that the incomes of the superrich are qualitatively different from others. Some are “superstars,” for whom small differences in talent are magnified into much larger earnings differences, while others work in winner-take-all markets, meaning that their effort to climb the ladder of success reduces the returns to others. Moreover, the discussion about tax rates must be accompanied by attention to the tax base, with a special focus on capital gains, which comprise a large fraction of the taxable income of the superrich. We also review the pros and cons of wealth taxes versus alternative policies that achieve similar objectives. While a dozen OECD countries levied wealth taxes in the recent past, only three retain them at present. Only Switzerland raises a similar fraction of revenue with its wealth tax as the recent U.S. proposals, therefore serving as a useful example.

Policy alternatives

Several alternatives to a wealth tax have been proposed to achieve its primary goal of increasing the progressivity of the U.S. tax system. The current system exhibits structural deficiencies in the treatment of capital gains. Many have therefore proposed fixing these defects directly. Indeed, Joe Biden has released plans to tax capital gains and dividends at the same rate as ordinary income for taxpayers with incomes exceeding $1 million and to tax unrealized capital gains at death. His plan would also increase income tax rates for taxpayers with incomes over $400,000 from 37% to 39.6%. Hence, the top marginal tax rate for capital gains would increase from 20% to 39.6%. However, his plan does not include a wealth tax.

While Biden’s plan would eliminate two of the preferential provisions for capital gains, it would retain the current system of taxation based on realization rather than accrual and thereby preserve the within-a-lifetime tax deferral advantage. Moreover, a realization-based treatment does not fix the problem of very low tax burdens for superrich individuals who neither receive much ordinary nor dividend income nor sell many shares of the businesses they own. In view of this, calls for the taxation of accrued capital gains have been made. An accrual-based capital gains tax is straightforward to implement for publicly traded assets because one can rely on market prices and third-party-reported transactions. For illiquid assets, however, such as privately held businesses, which are a significant source of returns for rich households, it runs into similar problems as a wealth tax because these assets are difficult to value objectively. Moreover, it might force entrepreneurs to continually reduce their share in a company whose valuation increases over time in order pay the tax liability, another feature it shares with a wealth tax. Even if monetary incentives are not the primary motivation for these entrepreneurs, who are instead mostly interested in being able to realize their ideas, such a dilution of control rights could have discouraging effects early on, for example, when young individuals decide whether to become entrepreneurs in the first place.

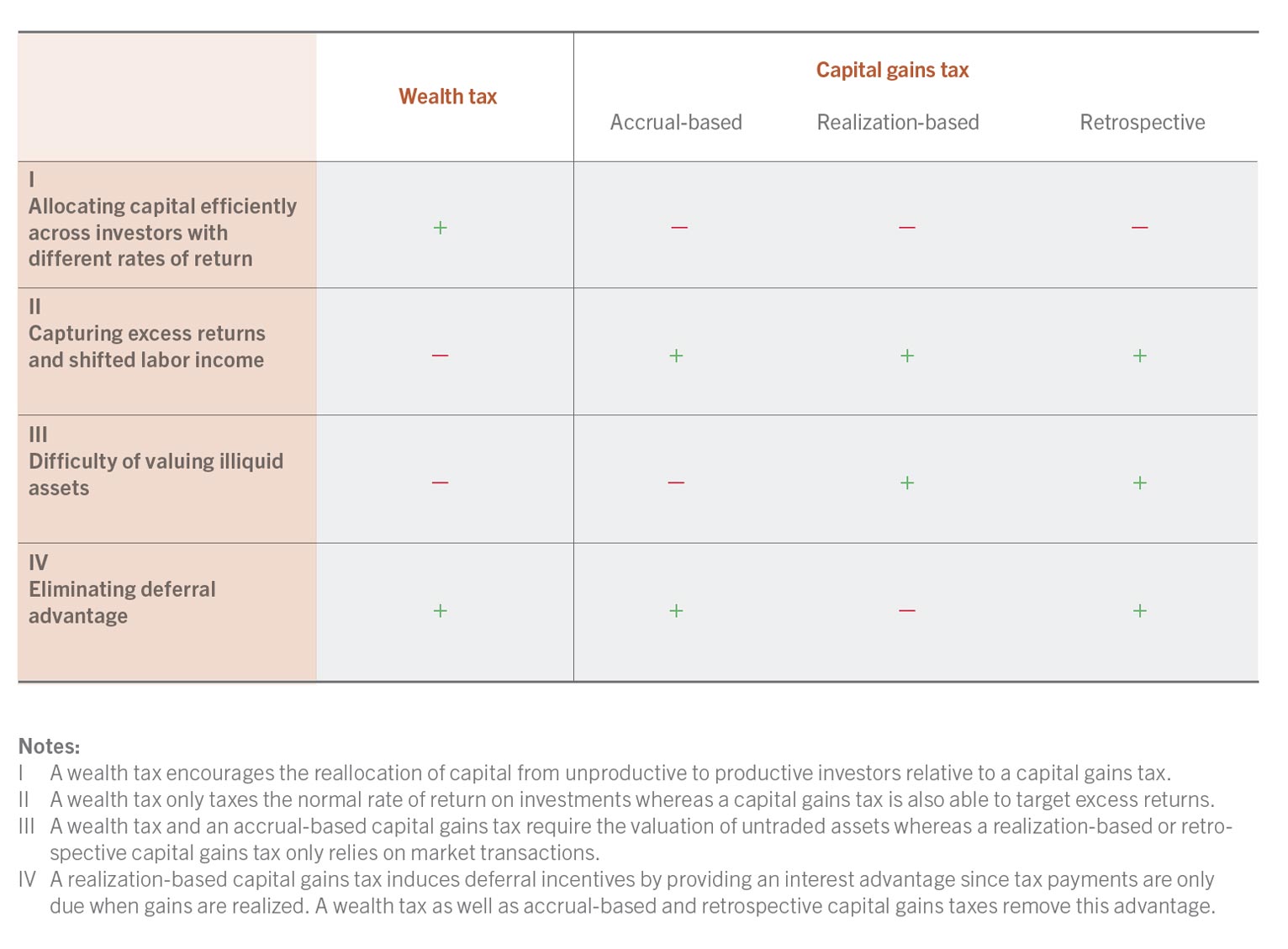

A potential solution to these problems is a retrospective accrual tax. Under such a scheme, the tax is assessed upon realization, but the statutory tax rate rises as the holding period lengthens, effectively charging interest on past gains when realization occurs. This eliminates the need to value assets except when sold while minimizing liquidity problems and the incentive to defer such realization. The table summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of wealth taxes versus these different forms of capital gains taxation.

Several alternatives to a wealth tax have been proposed to achieve its primary goal of increasing the progressivity of the U.S. tax system. The current system exhibits structural deficiencies in the treatment of capital gains. Many have therefore proposed fixing these defects directly. Indeed, Joe Biden has released plans to tax capital gains and dividends at the same rate as ordinary income for taxpayers with incomes exceeding $1 million and to tax unrealized capital gains at death. His plan would also increase income tax rates for taxpayers with incomes over $400,000 from 37% to 39.6%. Hence, the top marginal tax rate for capital gains would increase from 20% to 39.6%. However, his plan does not include a wealth tax.

While Biden’s plan would eliminate two of the preferential provisions for capital gains, it would retain the current system of taxation based on realization rather than accrual and thereby preserve the within-a-lifetime tax deferral advantage. Moreover, a realization-based treatment does not fix the problem of very low tax burdens for superrich individuals who neither receive much ordinary nor dividend income nor sell many shares of the businesses they own. In view of this, calls for the taxation of accrued capital gains have been made. An accrual-based capital gains tax is straightforward to implement for publicly traded assets because one can rely on market prices and third-party-reported transactions. For illiquid assets, however, such as privately held businesses, which are a significant source of returns for rich households, it runs into similar problems as a wealth tax because these assets are difficult to value objectively. Moreover, it might force entrepreneurs to continually reduce their share in a company whose valuation increases over time in order pay the tax liability, another feature it shares with a wealth tax. Even if monetary incentives are not the primary motivation for these entrepreneurs, who are instead mostly interested in being able to realize their ideas, such a dilution of control rights could have discouraging effects early on, for example, when young individuals decide whether to become entrepreneurs in the first place.

Webinar

Presse

«Die Erbschaftsteuer müsste viel beliebter sein» Die Zeit Interview mit Florian Scheuer vom 9.11.2020 lesen

Related videos

Author

Florian Scheuer received his PhD from MIT in 2010. He is interested in the policy implications of rising inequality, with a focus on tax policy. In particular, he has worked on incorporating important features of real-world labor markets into the design of optimal income and wealth taxes. These include economies with rent-seeking, superstar effects or an important entrepreneurial sector, frictional financial markets, as well as political constraints on tax policy and the resulting inequality. His work has been published in the American Economic Review, the Journal of Political Economy, the Quarterly Journal of Economics and the Review of Economic Studies, among other journals. In 2017, he received an ERC starting grant for his research on “Inequality - Public Policy and Political Economy.” Before joining Zurich, he was on the faculty at Stanford, held visiting positions at Harvard and UC Berkeley and was a National Fellow at the Hoover Institution. He is Co-Editor of Theoretical Economics and Member of the Board of Editors of the Review of Economic Studies. He is also a Co-Director of the working group on Macro Public Finance at the NBER. He has commented on tax policy in various US and Swiss media outlets.

Florian Scheuer received his PhD from MIT in 2010. He is interested in the policy implications of rising inequality, with a focus on tax policy. In particular, he has worked on incorporating important features of real-world labor markets into the design of optimal income and wealth taxes. These include economies with rent-seeking, superstar effects or an important entrepreneurial sector, frictional financial markets, as well as political constraints on tax policy and the resulting inequality. His work has been published in the American Economic Review, the Journal of Political Economy, the Quarterly Journal of Economics and the Review of Economic Studies, among other journals. In 2017, he received an ERC starting grant for his research on “Inequality - Public Policy and Political Economy.” Before joining Zurich, he was on the faculty at Stanford, held visiting positions at Harvard and UC Berkeley and was a National Fellow at the Hoover Institution. He is Co-Editor of Theoretical Economics and Member of the Board of Editors of the Review of Economic Studies. He is also a Co-Director of the working group on Macro Public Finance at the NBER. He has commented on tax policy in various US and Swiss media outlets.