10

Video summary

Economics and climate change

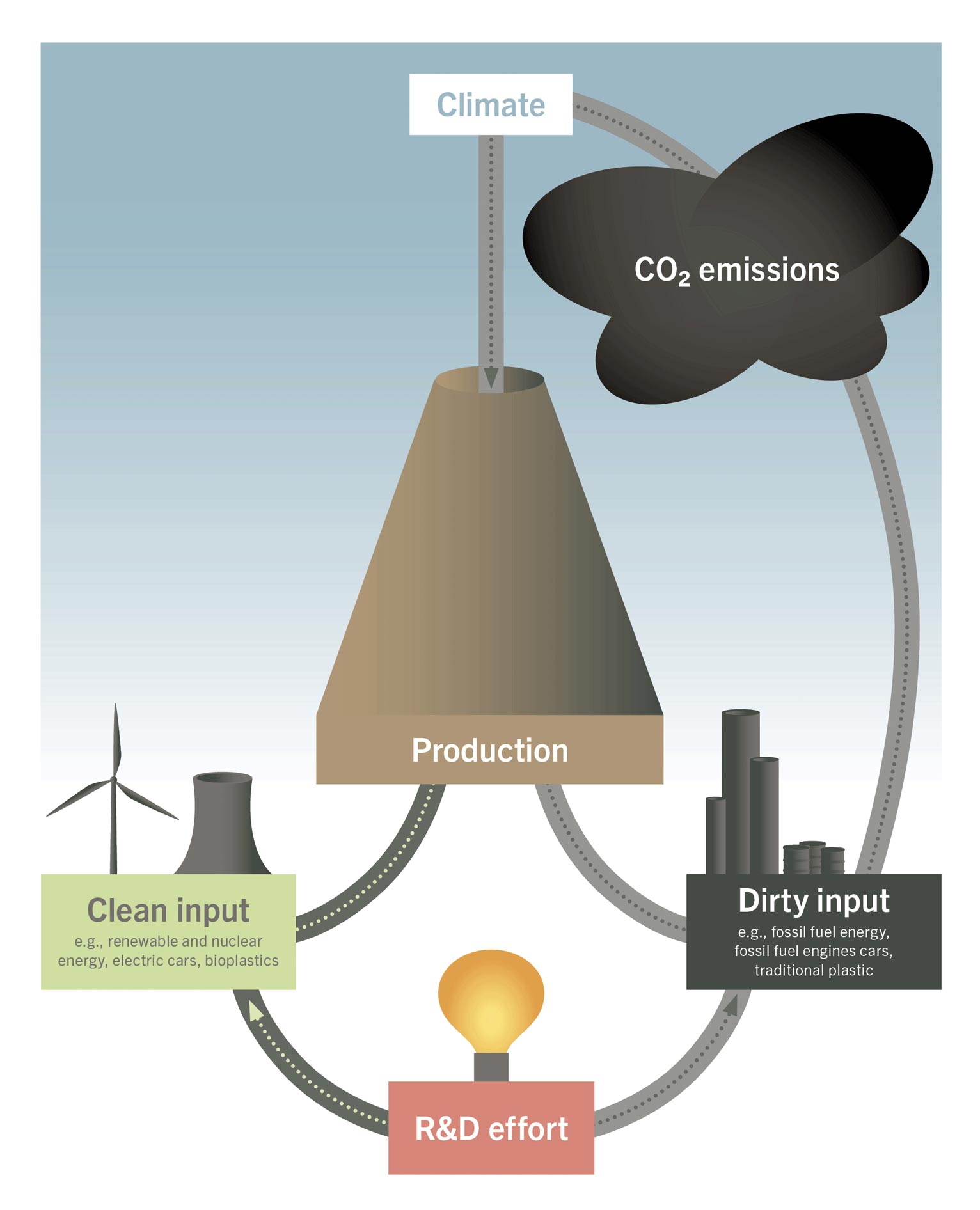

Climate change already has a negative impact on the environment and our societies, and this impact will get worse over the course of this century. How much worse? This will depend on our ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Achieving the necessary reduction in emissions, while maintaining (and improving) worldwide living standards can only be achieved through innovation. Fortunately, innovation is not manna from heaven; it is conducted by scientists and firms and it reacts to market and policy incentives. It is therefore up to governments to steer it toward clean technologies.

In this public paper, I will review recent economic research on the role of innovation in the design of climate policy. After a quick introduction to the challenges posed by climate change, I will show that current technological trends – though promising – are unlikely to be sufficient to limit warming to 2°C. Can policy then effectively boost green innovation? Recent evidence shows that this is definitely the case. How should global climate policy be designed to leverage this innovation response? What about unilateral policies? Some innovations are “grey”: they permit the replacement of particularly dirty technologies with less dirty but still polluting ones. The shale gas revolution is an example. Can these “grey” innovations backfire?

Climate change already has a negative impact on the environment and our societies, and this impact will get worse over the course of this century. How much worse? This will depend on our ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Achieving the necessary reduction in emissions, while maintaining (and improving) worldwide living standards can only be achieved through innovation. Fortunately, innovation is not manna from heaven; it is conducted by scientists and firms and it reacts to market and policy incentives. It is therefore up to governments to steer it toward clean technologies.

In this public paper, I will review recent economic research on the role of innovation in the design of climate policy. After a quick introduction to the challenges posed by climate change, I will show that current technological trends – though promising – are unlikely to be sufficient to limit warming to 2°C. Can policy then effectively boost green innovation? Recent evidence shows that this is definitely the case. How should global climate policy be designed to leverage this innovation response? What about unilateral policies? Some innovations are “grey”: they permit the replacement of particularly dirty technologies with less dirty but still polluting ones. The shale gas revolution is an example. Can these “grey” innovations backfire?

Innovation framework

The recent decline in green innovation is a clear reminder that policy is key to direct innovation toward decarbonization. Innovation has the potential to combine the necessary decline in greenhouse gas emissions with sustained economic growth; and it responds largely and rapidly to price signals. This is true both for a carbon tax but also, in the opposite direction, for a decline in the cost of fossil fuels. As a result, climate policy should be designed not only in view of reducing polluting activities today with instruments such as a carbon tax, but also in order to incentivize clean innovation. As we have seen, this means that governments should

- use front-loaded subsidies to clean research,

- implement unilateral green industrial policies in the absence of a global agreement and

- accompany the potential deployment of bridge technologies with renewed support for clean innovation.

Of course, tackling climate change is a complex problem, and this paper omits a number of interesting questions. One is whether it is economically in a country’s best interest to act unilaterally and develop clean technologies which can reduce emissions worldwide. On one hand, such endeavor allows a country to build a comparative advantage in sectors which are bound to become more important over time: the next “oil countries’’ are likely to be those able to deliver cheap clean energy to the world. On the other hand, there is no guarantee that an early edge in clean technologies will survive and pay off: for example, Germany and the US were the world leaders in solar photovoltaic cells in the 2000s, but they have since been overtaken by China.

Another important issue is society’s acceptance of climate policy. While youth demonstrations send a message to governments that they need to speed up the energy transition, attempts to implement measures such as carbon taxes have also generated violent backlash as illustrated by the “yellow vest’’ movement in France. A policy focused on innovation may be easier to accept, but as important as innovation is, economic analysis also emphasizes that emissions should start declining now and carbon pricing is the right tool to achieve reductions in the short-term.

The recent decline in green innovation is a clear reminder that policy is key to direct innovation toward decarbonization. Innovation has the potential to combine the necessary decline in greenhouse gas emissions with sustained economic growth; and it responds largely and rapidly to price signals. This is true both for a carbon tax but also, in the opposite direction, for a decline in the cost of fossil fuels. As a result, climate policy should be designed not only in view of reducing polluting activities today with instruments such as a carbon tax, but also in order to incentivize clean innovation. As we have seen, this means that governments should

- use front-loaded subsidies to clean research,

- implement unilateral green industrial policies in the absence of a global agreement and

- accompany the potential deployment of bridge technologies with renewed support for clean innovation.

Of course, tackling climate change is a complex problem, and this paper omits a number of interesting questions. One is whether it is economically in a country’s best interest to act unilaterally and develop clean technologies which can reduce emissions worldwide. On one hand, such endeavor allows a country to build a comparative advantage in sectors which are bound to become more important over time: the next “oil countries’’ are likely to be those able to deliver cheap clean energy to the world. On the other hand, there is no guarantee that an early edge in clean technologies will survive and pay off: for example, Germany and the US were the world leaders in solar photovoltaic cells in the 2000s, but they have since been overtaken by China.

Related videos

Author

David Hémous received his PhD from Harvard University in 2012. He is a macroeconomist working on economic growth, climate change and inequality. His work highlights that innovation responds to economic incentives and that public policies should be designed taking this dependence into account. In particular, he has shown in the context of climate change policy that innovations in the car industry respond to gas prices and that global and regional climate policies should support clean innovation to efficiently reduce CO2 emissions. His work on technological change and income distribution shows that higher labor costs lead to more automation, and that the recent increase in labor income inequality and in the capital share can be explained by a secular increase in automation. He has also shown that innovation affects top income shares. He was awarded an ERC Starting Grant on 'Automation and Income Distribution – a Quantitative Assessment' and he received the 2022 'European Award for Researchers in Environmental Economics under the Age of Forty'.

David Hémous received his PhD from Harvard University in 2012. He is a macroeconomist working on economic growth, climate change and inequality. His work highlights that innovation responds to economic incentives and that public policies should be designed taking this dependence into account. In particular, he has shown in the context of climate change policy that innovations in the car industry respond to gas prices and that global and regional climate policies should support clean innovation to efficiently reduce CO2 emissions. His work on technological change and income distribution shows that higher labor costs lead to more automation, and that the recent increase in labor income inequality and in the capital share can be explained by a secular increase in automation. He has also shown that innovation affects top income shares. He was awarded an ERC Starting Grant on 'Automation and Income Distribution – a Quantitative Assessment' and he received the 2022 'European Award for Researchers in Environmental Economics under the Age of Forty'.