7

Video summary

Putting cooperation and feedback center stage

A sound corporate culture drives a company’s overall performance sustainably – this is not only common sense, but also evidenced in research. Why is culture so important for economic success, and what are the characteristics of a successful corporate culture? A new paper by Ernst Fehr puts cooperation and feedback center stage.

In the seventh edition of the UBS Center Public Paper series, Ernst Fehr steps into the corporate world. He argues that corporate culture strongly drives employees’ behavior, thus designing the right corporate culture is in every company’s best interest. But what does it take to achieve a successful corporate culture? Dipping into the fascinating field of behavioral and experimental economics, Fehr explains how the right behavioral rules and incentives can foster productive cooperation among employees and at the same time limit free-rider effects or similar unwanted behavior.

Corporate culture, trust, and success

Among the many different aspects of a corporate culture, cooperation is one of the core elements for performance and success. A cooperative culture helps to build trust in an organization: employees trust that their colleagues will also behave in line with the organization’s values, and this trust itself reinforces obedience to the cooperative culture and strengthens it. Research shows that firms in which the employees perceive their top managers as trustworthy and ethical in their business practices are more productive. Another study shows that countries, which uphold values that lead to a high level of cooperation and trustworthiness – and thus trust – flourish significantly better. This is the case in most northern European countries, such as Norway, Sweden, and Finland – in sharp contrast to countries like Liberia or Rwanda.

How to make it work

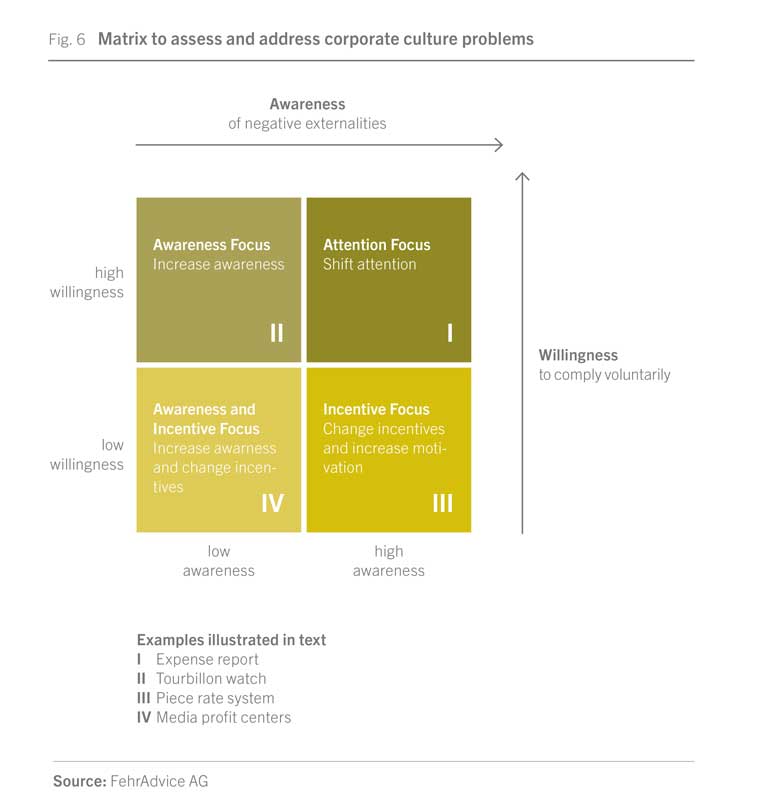

While every company has some sort of corporate culture, there is a big variance in their design. Unsurprisingly, they also face different corporate culture problems – like free-riding or the lack of cooperation among coworkers. Some problems are easily solved with simple nudges and awareness campaigns, such as providing feedback opportunities to identify free riders. However, others require implementing a new set of strong social norms with associated enforcement rules. Fehr introduces a matrix to assess and address corporate culture problems. He classifies problems along two dimensions: the employees’ average willingness to comply voluntarily with the cooperative social norms, and the employees’ awareness of the negative effects that result from non-compliance. Depending on the category in which a problem falls, Fehr proposes different measures, such as changing norm-driven and financial incentives or raising awareness for the needs of other business units within a firm.

A final important takeout from Fehr’s paper is that the mere proclamation of abstract values – such as integrity, loyalty, or commitment – does not suffice for achieving a cooperative culture. Values need to be translated into concrete behaviors, they need to be widely shared, lived, integrated into everyday actions, and enforced by both top management and the employees. Moreover, to make it work, the behavioral rules must be clear and simple.

A sound corporate culture drives a company’s overall performance sustainably – this is not only common sense, but also evidenced in research. Why is culture so important for economic success, and what are the characteristics of a successful corporate culture? A new paper by Ernst Fehr puts cooperation and feedback center stage.

In the seventh edition of the UBS Center Public Paper series, Ernst Fehr steps into the corporate world. He argues that corporate culture strongly drives employees’ behavior, thus designing the right corporate culture is in every company’s best interest. But what does it take to achieve a successful corporate culture? Dipping into the fascinating field of behavioral and experimental economics, Fehr explains how the right behavioral rules and incentives can foster productive cooperation among employees and at the same time limit free-rider effects or similar unwanted behavior.

Corporate culture, trust, and success

Among the many different aspects of a corporate culture, cooperation is one of the core elements for performance and success. A cooperative culture helps to build trust in an organization: employees trust that their colleagues will also behave in line with the organization’s values, and this trust itself reinforces obedience to the cooperative culture and strengthens it. Research shows that firms in which the employees perceive their top managers as trustworthy and ethical in their business practices are more productive. Another study shows that countries, which uphold values that lead to a high level of cooperation and trustworthiness – and thus trust – flourish significantly better. This is the case in most northern European countries, such as Norway, Sweden, and Finland – in sharp contrast to countries like Liberia or Rwanda.

Abstract

Talking about corporate culture has become quite popular in the business world. But why should companies care about corporate culture at all? Why do “soft” concepts like culture matter? Can’t companies simply rely on “hard” facts – the value of clear and efficient institutional rules and incentives? In this Public Paper, we argue that corporate culture is important because human behavior is always co-determined by the prevailing social norms. It is in the company’s interest to shape these norms through a cooperative culture that mobilizes employees’ voluntary cooperation in the pursuit of the firm’s performance goals. Our research provides behavioral foundations for cooperative cultures, based on important scientific insights from contract economics as well as from experimental and behavioral economics. In particular, contractual incompleteness, the imperfections of centralized monitoring, and limits to contract enforcement naturally constrain firms’ ability to regulate and direct their employees’ behavior. This causes severe free-rider problems, which can be solved with cooperative corporate cultures based on social norms that increase the company’s overall performance. We show that a large share of the people is typically willing to follow prosocial norms at least partially if they believe that other people and, in particular the top leaders, will also comply. An important reason to legitimize cooperative norms, perhaps the most important one, is that they transparently increase the firm’s overall value and generate long-run benefits for the involved parties.

As a firm’s workforce is typically composed of people with different propensities for voluntary cooperation, it is inevitable that some of them will free ride on others’ efforts if sanctions do not enforce rules and norms. The failure to comply with norms has the tendency to spread if appropriate measures do not constrain it. However, forces similar to those that lead to contractual incompleteness and imperfect monitoring also limit the centralized enforcement of norms. Peer feedback and peer sanctioning are therefore required for implementing and enforcing a cooperative culture. The optimal conditions for the effectiveness of peer feedback exist when it is an integral part of a company’s corporate culture and when all involved parties recognize that peer feedback increases the firm’s overall performance and all stakeholders benefit from it.

Classifying corporate culture problems along the two dimensions “willingness to cooperate” and “awareness of negative externalities” has proven to be useful for determining the appropriate set of measures for solving these problems. Depending on the problem, the measures are in the areas of “changing awareness”, “changing incentives and motivation”, or both.

A final important lesson is that the mere proclamation of abstract values does not suffice for achieving a cooperative culinto concrete behavioral rules on the “shop floor” that are widely shared and enforced by top management and the employees themselves. To engineer compliance, the behavioral rules must be clear and simple. Further, they must transparently contribute to a firm-specific public good, such that employees can agree with them – because otherwise they will not enforce them.

Talking about corporate culture has become quite popular in the business world. But why should companies care about corporate culture at all? Why do “soft” concepts like culture matter? Can’t companies simply rely on “hard” facts – the value of clear and efficient institutional rules and incentives? In this Public Paper, we argue that corporate culture is important because human behavior is always co-determined by the prevailing social norms. It is in the company’s interest to shape these norms through a cooperative culture that mobilizes employees’ voluntary cooperation in the pursuit of the firm’s performance goals. Our research provides behavioral foundations for cooperative cultures, based on important scientific insights from contract economics as well as from experimental and behavioral economics. In particular, contractual incompleteness, the imperfections of centralized monitoring, and limits to contract enforcement naturally constrain firms’ ability to regulate and direct their employees’ behavior. This causes severe free-rider problems, which can be solved with cooperative corporate cultures based on social norms that increase the company’s overall performance. We show that a large share of the people is typically willing to follow prosocial norms at least partially if they believe that other people and, in particular the top leaders, will also comply. An important reason to legitimize cooperative norms, perhaps the most important one, is that they transparently increase the firm’s overall value and generate long-run benefits for the involved parties.

As a firm’s workforce is typically composed of people with different propensities for voluntary cooperation, it is inevitable that some of them will free ride on others’ efforts if sanctions do not enforce rules and norms. The failure to comply with norms has the tendency to spread if appropriate measures do not constrain it. However, forces similar to those that lead to contractual incompleteness and imperfect monitoring also limit the centralized enforcement of norms. Peer feedback and peer sanctioning are therefore required for implementing and enforcing a cooperative culture. The optimal conditions for the effectiveness of peer feedback exist when it is an integral part of a company’s corporate culture and when all involved parties recognize that peer feedback increases the firm’s overall performance and all stakeholders benefit from it.

Press

Behavioral Foundations of Corporate Culture Harvard Law School Forum vom 12.3.2019 read

Summary

Contractual incompleteness, the imperfections of centralized monitoring, and limits to contract enforcement naturally constrain firms’ ability to regulate and direct their employees’ behavior. This causes severe free-rider problems, which cooperative corporate cultures can overcome by defining and implementing social norms geared towards increasing the company’s overall performance. A large share of the people is typically willing to follow prosocial norms at least partially if they believe that other people and, in particular the top leaders, will also comply. An important ingredient, perhaps the most important one, to legitimize cooperative norms is that they transparently increase the firm’s overall value and generate long-run benefits for the involved parties.

As a firm’s workforce is typically composed of people with different propensities for voluntary cooperation, it is inevitable that some of them will free ride on others’ efforts if sanctions do not enforce rules and norms. The failure to comply with norms has the tendency to spread if appropriate measures do not constrain it. However, forces similar to those that lead to contractual incompleteness and imperfect monitoring also limit the centralized enforcement of norms. Peer feedback and peer sanctioning are, therefore, required for implementing and enforcing a cooperative culture. The optimal conditions for the effectiveness of peer feedback exist when it becomes an integral part of a company’s corporate culture by making it a social norm and when all involved parties recognize that peer feedback increases the firm’s overall performance and all stakeholders benefit from it. Classifying corporate culture problems along the two dimensions “willingness to cooperate” and “awareness of negative externalities” has proven to be useful for determining the appropriate set of measures for solving these problems. Depending on the problem, the measures are in the areas of “changing awareness”, “changing incentives and motivation” or both.

A final important lesson is that the mere proclamation of abstract values does not suffice for achieving a cooperative culture. These values need to be translated into concrete behavioral rules on the “shop floor” that are widely shared and enforced by top management and the employees themselves. To engineer compliance, the behavioral rules must be clear and simple. Further, they must transparently contribute to a firm-specific public good, such that employees can agree with them – because otherwise they will not enforce them.

Contractual incompleteness, the imperfections of centralized monitoring, and limits to contract enforcement naturally constrain firms’ ability to regulate and direct their employees’ behavior. This causes severe free-rider problems, which cooperative corporate cultures can overcome by defining and implementing social norms geared towards increasing the company’s overall performance. A large share of the people is typically willing to follow prosocial norms at least partially if they believe that other people and, in particular the top leaders, will also comply. An important ingredient, perhaps the most important one, to legitimize cooperative norms is that they transparently increase the firm’s overall value and generate long-run benefits for the involved parties.

As a firm’s workforce is typically composed of people with different propensities for voluntary cooperation, it is inevitable that some of them will free ride on others’ efforts if sanctions do not enforce rules and norms. The failure to comply with norms has the tendency to spread if appropriate measures do not constrain it. However, forces similar to those that lead to contractual incompleteness and imperfect monitoring also limit the centralized enforcement of norms. Peer feedback and peer sanctioning are, therefore, required for implementing and enforcing a cooperative culture. The optimal conditions for the effectiveness of peer feedback exist when it becomes an integral part of a company’s corporate culture by making it a social norm and when all involved parties recognize that peer feedback increases the firm’s overall performance and all stakeholders benefit from it. Classifying corporate culture problems along the two dimensions “willingness to cooperate” and “awareness of negative externalities” has proven to be useful for determining the appropriate set of measures for solving these problems. Depending on the problem, the measures are in the areas of “changing awareness”, “changing incentives and motivation” or both.

Key findings

Authors

Ernst Fehr received his doctorate from the University of Vienna in 1986. His work has shown how social motives shape the cooperation, negotiations and coordination among actors and how this affects the functioning of incentives, markets and organisations. His work identifies important conditions under which cooperation flourishes and breaks down. The work on the psychological foundations of incentives informs us about the merits and the limits of financial incentives for the compensation of employees. In other work he has shown the importance of corporate culture for the performance of firms. In more recent work he shows how social motives affect how people vote on issues related to the redistribution of incomes and how differences in people’s intrinsic patience is related to wealth inequality. His work has found large resonance inside and outside academia with more than 100’000 Google Scholar citations and his work has been mentioned many times in international and national newspapers.

Ernst Fehr received his doctorate from the University of Vienna in 1986. His work has shown how social motives shape the cooperation, negotiations and coordination among actors and how this affects the functioning of incentives, markets and organisations. His work identifies important conditions under which cooperation flourishes and breaks down. The work on the psychological foundations of incentives informs us about the merits and the limits of financial incentives for the compensation of employees. In other work he has shown the importance of corporate culture for the performance of firms. In more recent work he shows how social motives affect how people vote on issues related to the redistribution of incomes and how differences in people’s intrinsic patience is related to wealth inequality. His work has found large resonance inside and outside academia with more than 100’000 Google Scholar citations and his work has been mentioned many times in international and national newspapers.