Better answers to our biggest problems

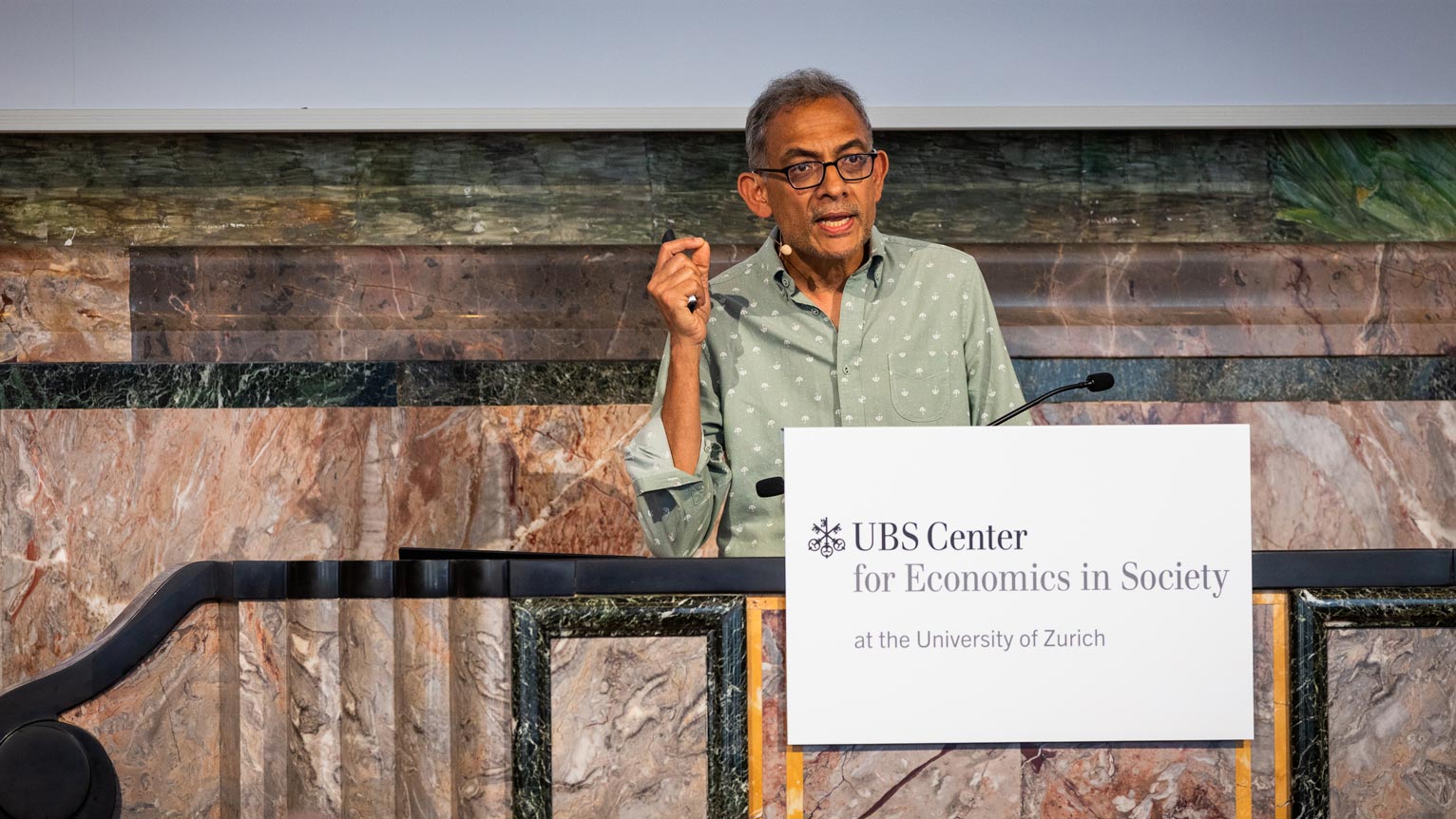

Why do we find it so difficult to solve pressing global problems? Nobel laureate in economics Abhijit Banerjee explains the reasons.

This interview by Albert Steck was originally published in German by Swiss weekly «NZZ am Sonntag», 2 July 2022. Translated and edited for layout purposes by the UBS Center.

Your latest book is entitled "Good Economics for Hard Times. What prompted you to write a book about hard times?

The fact that our world is facing major problems has been apparent for some time. When I wrote the book with Esther Duflo, the U.S. was in the midst of the era of Donald Trump. We were interested in the question: Why have such strong populist movements emerged in numerous countries in a short period of time? Obviously, there is a great deal of uncertainty among many people. Economics must find answers to how we can respond to these challenges.

Let's look at the list of current problems - it's a long one: First, there's the war in Ukraine. This is leading to inflation and famine. The pandemic has also exacerbated social inequality. You have already mentioned the growing populism. Which of these issues should we tackle first?

There are two answers to this: Climate change will have the most serious consequences in the long term. Here, economics would have good solutions at hand to address the problem. But the political process is stuck. So my second answer is that we first need more credible policies to reduce social inequality. Because these two issues are linked. If we want to fight climate change effectively, people must not worry about what distributional effects the measures will have on them. Otherwise, the losers will block any change.

Why do you think politicians are doing too little to combat social inequality?

This brings us back to populism, which undermines the democratic values of a society: It is mainly the poorer people who vote for populist politicians. They feel cheated by economic development. They hear promises that everyone will benefit from economic progress. But because they feel too little of it, they have lost confidence in politics.

Which inequality worries you more: the one within a country or the one between rich and poor nations?

At the global level, the picture is mixed: both the very poor and the very rich have benefited in recent decades. By contrast, the global middle class has lost out. In the U.S., the working class has declined, while in India, the upper middle class has come under pressure.

As a development economist, do you see a danger that the rift between the North and the South will deepen?

During the pandemic, there was a strong vaccine nationalism. This lack of support for the poorer countries has hurt global cooperation, for example in the fight against climate change. The next test case now is food supply: From an economic point of view, there would be perfectly good solutions in the fight against the impending shortage.

Are you referring here to the fact that about 40 percent of grain is used for animal feed and as biofuel?

An increase in the price of meat would lead to a shift in demand so that more grain would be available for other foods. However, I think such a solution is illusory at present, because nutrition is a toxic issue. Therefore, I see little political will to combat famine, which is particularly imminent in the Sahel. The tragedy of this crisis is that it would take relatively small amounts of money to achieve a better global food supply.

However, the lack of grain cannot be blamed on the European countries. After all, these are also suffering from the Russian attack on Ukraine.

I don't think the southern countries are expecting a huge wave of aid. But it is also about the credibility of the democratic values of the West in the rest of the world. Vaccine nationalism has already damaged that reputation. Against this background, we should not be surprised that only a few countries have joined in the Western sanctions against Russia.

How fragile is the political situation in developing countries: Do you expect the explosion in food prices to lead to uprisings?

I hope not. But the global community must act now to avert disaster. According to the Save the Children organization, half a million children are acutely threatened by hunger. What's more, the costs of preventing a crisis are much lower than the damage once an emergency has broken out.

Inflation also affects people in rich countries. Does it make sense for the German government to cushion the price shock of gasoline with fuel discounts?

From an economic point of view, the question is comparable to the food price spike: Is there a solution to distribute the scarce gasoline in such a way that poorer people in Germany do not suffer? My answer is: Yes, we know proven methods to specifically ensure that the lower income groups can still afford gasoline. Such measures are more efficient and cost-effective than a blanket fuel rebate for everyone.

You say that good economic solutions to such scarcity problems exist. Yet they receive little attention in the political arena. There, subsidies with a watering can are more popular. Does that frustrate you?

To be honest, yes. On the other hand, economists themselves are to blame for the fact that their discipline has lost credibility. Our guild has been guided by ideological arguments for too long and has neglected the interests of the disadvantaged, for example.

Globalization in particular has disappointed many people.

That's true. Economists like to emphasize the benefits of trade. But the benefit of getting a T-shirt one franc cheaper is spread over many heads. The textile worker, on the other hand, who loses his job because of this, feels the consequences very directly. We have paid far too little attention to how we can compensate the losers of globalization.

Do you want to reverse globalization?

Such a thing would no longer be possible. Instead, we need purposeful instruments to help the losers. In the USA, such programs already exist and are very successful. Unfortunately, they have been used far too infrequently up to now.

That is one of the reasons for the rise of populist movements. So are their concerns valid?

Populists usually look for the cause of problems among immigrants or minorities. In doing so, they primarily stir up anger and fears. But we can't solve problems with restrictive laws. Nor does the ban on abortion in the USA help anyone. Such illiberal actions only lead to more oppression, in this case of young women.

Liberal values are also catching less and less in Western nations. Why?

Most rich countries have failed to put in place convincing social policies. There have hardly been any programs to support the outlying regions, for example in eastern Germany or northern France. At least the rural provinces in Europe are still better intact than in the U.S., where entire areas are in decline. Liberal politicians have far too often neglected the needs of these people.

What is your prognosis: How difficult will the road be to get out of these hard times?

The situation certainly looks very bad at the moment. But we have to take into account that the last 20 years have been particularly good. Global poverty and child mortality have fallen sharply. Deaths from malaria have halved. One reason for this is the global initiatives, which have had great success. That's what we should be looking to now: With the right measures, we can help many people or even save lives even in this crisis.

Where should we apply the lever first?

We absolutely must try to find solutions to the hunger crisis – and we could achieve this very cheaply.

You made the cheeky remark that economics is too important to be left to the economists. You also question classic economic beliefs, such as globalization. Do you see yourself as a lateral thinker?

Maybe I'd like to be, but I'm not at all. I have been a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which is one of the most renowned faculties in the world, for 30 years now. The view that trade has negative effects or that we need to address social inequality is shared by the majority of colleagues at my university. Economics has evolved a lot in recent years. It is now much less ideological on many issues than it may still be perceived to be by the public.

Why do we find it so difficult to solve pressing global problems? Nobel laureate in economics Abhijit Banerjee explains the reasons.

This interview by Albert Steck was originally published in German by Swiss weekly «NZZ am Sonntag», 2 July 2022. Translated and edited for layout purposes by the UBS Center.

Your latest book is entitled "Good Economics for Hard Times. What prompted you to write a book about hard times?

Good economics for hard times

Contact

Abhijit Banerjee is the Ford Foundation International Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 2003 he co-founded the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) with Esther Duflo and Sendhil Mullainathan, and he remains one of the Lab’s Directors. Banerjee is a fellow of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Econometric Society. He is a winner of the Infosys Prize and co-recipient of the 2019 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel for his groundbreaking work in development economics research.

Abhijit Banerjee is the Ford Foundation International Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 2003 he co-founded the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) with Esther Duflo and Sendhil Mullainathan, and he remains one of the Lab’s Directors. Banerjee is a fellow of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Econometric Society. He is a winner of the Infosys Prize and co-recipient of the 2019 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel for his groundbreaking work in development economics research.