Some surprising lessons from history

High debt levels and violent conflicts are two of the themes that have been dominating the headlines for months. It goes without saying that both are seen as indicators of failure or decline. But as economic historian Hans-Joachim Voth shows, this does not always hold true. On the contrary, there were times when military conflict acted as an engine for development and high debt levels spurred economic growth.

by Maura Wyler

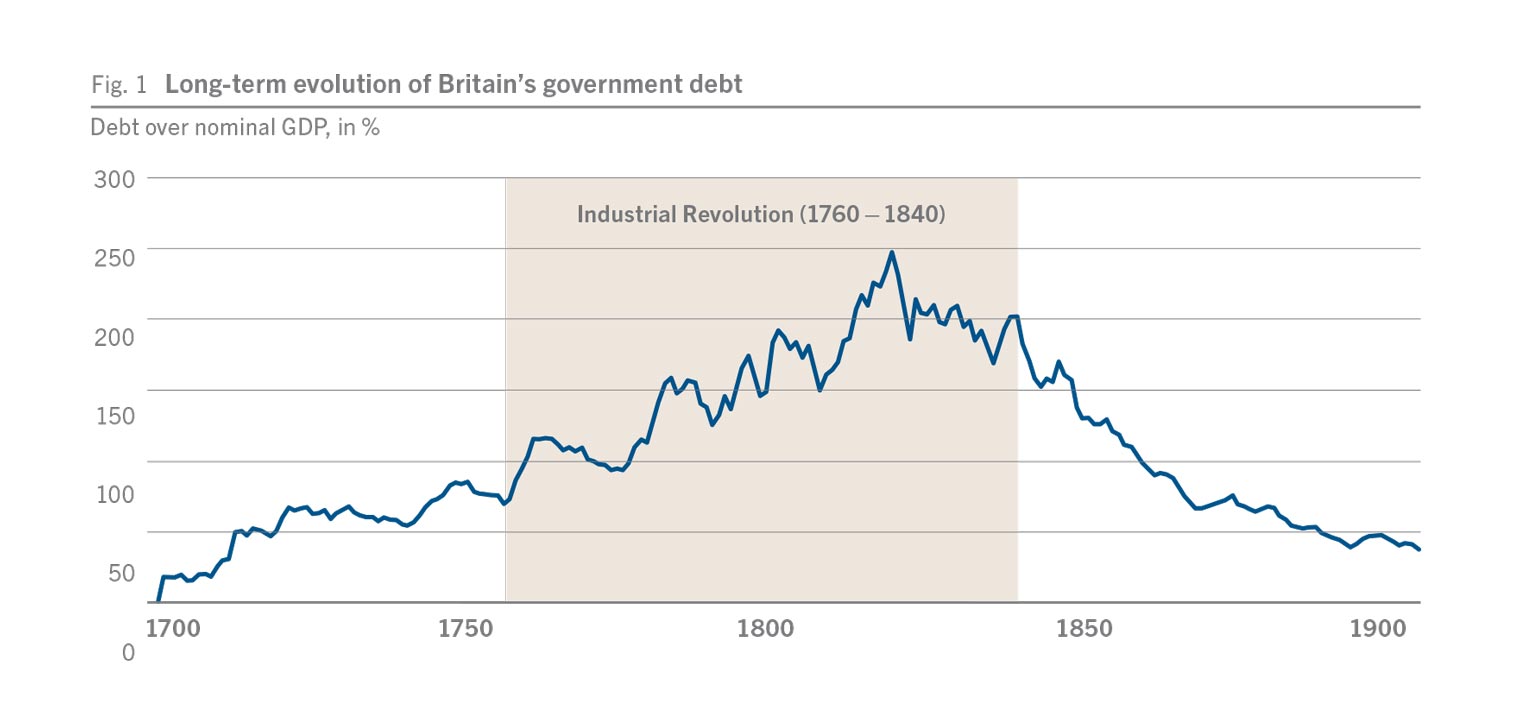

The relationship between conflict and development is the focus of Voth’s new article State Capacity and Military Conflict (co-authored with Nicola Gennaioli). By analyzing a wealth of data from the sixteenth to the early nineteenth centuries, he comes up with a rather bleak overall picture: Europe was characterized by high debt, drastic increases in tax rates, and long and expensive wars. The situation looked particularly dramatic for Britain: Between 1692 and 1815, Britain was involved in wars abroad in two out of every three years. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, Britain’s sovereign debt increased dramatically, from 5% in 1700 to 200% in 1820 (see Fig. 1). Tax rates also increased rapidly, but not quickly enough to keep pace with the increased expenditures.

However, readers well versed in history will be aware of the fact that the very same time period also saw the emergence of both the modern state and the Industrial Revolution. The leading nation in both developments? Britain. How can these unexpected patterns be explained?

States made war, and war made states

From the sixteenth century onwards, the so-called “Military Revolution” started to fundamentally change the way European powers waged wars: Gunpowder was invented, the legions of mercenaries from the Middle Ages were replaced by more professional, standing armies, and on top, these armies became much larger. All of these developments increased the cost of equipping and maintaining armies, so that money became an evermore dominating factor. As a result, only rulers who could procure large funds – either by creating an efficient tax system or by being able to borrow large sums – could hope for military success.

Because the ability to finance war was now key for survival, armed conflicts forced monarchs to create large funding bases, more professional bureaucracies, and better legal institutions – in other words, to lay the foundations for modern states as we know them today.

However, this growth in state capacity was highly uneven. It was the already stronger, less fragmented powers that were able to invest more in greater state capacity, while weaker powers rationally dropped out of the competition. Britain, France, and Prussia belonged to the strong, cohesive states, while Spain and Poland were unable to build-up their state capacity decisively. These divergences led to dramatic differences in military clout and determined their political fate.

Sovereign debt may be good if financial markets are dysfunctional

Britain was a case in point for the link between state capacity and success in the battlefield. However, as Britain raised most of its funds in the form of government bonds, its debt levels had reached an eye-watering 200% of GDP (see Fig. 1) when it defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. While such prolific fund-raising was a crucial factor for its military success, surely though such debt levels must have been a huge drain on the country’s economy. “Wrong again,” seems to be the answer we get from another one of Voth’s research projects. In the working paper Debt into Growth: How sovereign debt accelerated the first industrial revolution, Voth and his co-author Jaume Ventura argue that high sovereign debt may actually have accelerated structural change and economic growth in eighteenthcentury Britain.

At that time, England was characterized by a dysfunctional financial market. The banking sector was still small, inefficient, and burdened with restrictions on credit provision (for example by the usury laws). Additionally, the South Sea Bubble that had struck Britain’s stock market in 1719 led to the introduction of heavy-handed regulations that henceforth stifled the country’s capital markets severely. This meant that the new and highly profitable technologies – cotton manufacturing, iron production, coalmining, and transportation – were more or less cut off from the standard funding sources, i.e. from both credit and capital markets. On top, prejudices against these new technologies and their representatives prevented the rich upper class from investing their money in some more direct form in these new sectors. These enterprises thus had to largely finance themselves, even though their rate of return increased from 10% (1770) to 20% (1830) and was thus much higher than in the two dominant asset classes of the time – land and government bonds.

So far, so bad. However, in this state of dysfunctional credit and capital markets, it was the fast-rising market for government bonds that was at least able to help the entrepreneurs in an indirect way, namely through the labor market. The argument runs as follows. Traditionally, the main holders of the national wealth, the upper class, invested in land and its cultivation. With a return on investment of about 2%, this was not profitable, but status in England was always directly coupled with land ownership.

Due to the higher returns on government securities and their increasing availability and liquidity, the majority of the upper class changed their investment strategies around 1750. They did not continue investing in the purchase and maintenance of land, but in government securities that promised a higher yield, reducing the extent of the chronic excess investment in the farm sector. This decreased labor opportunities and wages in the farm sector, leaving large numbers of agricultural workers unemployed, forcing them to move away from the countryside into the cities in order to find work in industry. While difficult for laborers, this was good news for the industrialists. As they suddenly had a large number of cheap laborers available for the new factory jobs, their production costs fell as a result of lower labor costs, and their profits rose accordingly.

Due to the inability to raise funds in capital and credit markets, it was the reinvestment of exactly these profits in their own enterprises that kept this new emerging sector afloat. In the presence of this dysfunctional financial sector, the rapidly increasing state debt, which created a new large and liquid investment class in the form of government bonds, therefore supported the process of structural change away from less productive agrarian activities into new, more productive industries. And it was precisely these new industries that spearheaded the most fundamental structural change in history, namely the Industrial Revolution that originated in eighteenth-century England and thereafter started to spread around Europe, and then around the world.

Good and bad debt

History thus shows that under particular circumstances, high debt levels may not be a stumbling block for economic development, but may even enhance it. Based on this insight, Voth advocates developing a more unbiased approach towards sovereign debt, one that not only considers its dangers, but also keeps an eye on potential benefits. He lists three such potential benefits: First, temporary increases in sovereign debt are often less painful than brutal reductions in government spending or excessive tax increases, and these increases may guarantee more continuity for enterprises. Second, government securities can play an important role in the willingness to accept risk on the part of enterprises and investors, as holding secure bonds allow them to take on higher risk in other positions. Third, the example above has shown that, in the presence of underdeveloped or badly functioning financial markets, it may be preferable for people to invest in government bonds if the available alternative asset classes have (more) detrimental effects on the economy.

High debt levels and violent conflicts are two of the themes that have been dominating the headlines for months. It goes without saying that both are seen as indicators of failure or decline. But as economic historian Hans-Joachim Voth shows, this does not always hold true. On the contrary, there were times when military conflict acted as an engine for development and high debt levels spurred economic growth.

by Maura Wyler

The relationship between conflict and development is the focus of Voth’s new article State Capacity and Military Conflict (co-authored with Nicola Gennaioli). By analyzing a wealth of data from the sixteenth to the early nineteenth centuries, he comes up with a rather bleak overall picture: Europe was characterized by high debt, drastic increases in tax rates, and long and expensive wars. The situation looked particularly dramatic for Britain: Between 1692 and 1815, Britain was involved in wars abroad in two out of every three years. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, Britain’s sovereign debt increased dramatically, from 5% in 1700 to 200% in 1820 (see Fig. 1). Tax rates also increased rapidly, but not quickly enough to keep pace with the increased expenditures.

Key finding

References

Contact

Joachim Voth received his PhD from Oxford in 1996. He works on financial crises, long-run growth, as well as on the origins of political extremism. He has examined public debt dynamics and bank lending to the first serial defaulter in history, analysed risk-taking behaviour by lenders as a result of personal shocks, and the investor performance during speculative bubbles. Joachim has also examined the deep historical roots of anti-Semitism, showing that the same cities where pogroms occurred in the Middle Age also persecuted Jews more in the 1930s; he has analyzed the extent to which schooling can create radical racial stereotypes over the long run, and how dense social networks (“social capital”) facilitated the spread of the Nazi party. In his work on long-run growth, he has investigated the effects of fertility restriction, the role of warfare, and the importance of state capacity. Joachim has published more than 80 academic articles and 3 academic books, 5 trade books and more than 50 newspaper columns, op-eds and book reviews. His research has been highlighted in The Economist, the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, El Pais, Vanguardia, La Repubblica, the Frankfurter Allgemeine, NZZ, der Standard, der Spiegel, CNN, RTN, Swiss and German TV and radio.

Joachim Voth received his PhD from Oxford in 1996. He works on financial crises, long-run growth, as well as on the origins of political extremism. He has examined public debt dynamics and bank lending to the first serial defaulter in history, analysed risk-taking behaviour by lenders as a result of personal shocks, and the investor performance during speculative bubbles. Joachim has also examined the deep historical roots of anti-Semitism, showing that the same cities where pogroms occurred in the Middle Age also persecuted Jews more in the 1930s; he has analyzed the extent to which schooling can create radical racial stereotypes over the long run, and how dense social networks (“social capital”) facilitated the spread of the Nazi party. In his work on long-run growth, he has investigated the effects of fertility restriction, the role of warfare, and the importance of state capacity. Joachim has published more than 80 academic articles and 3 academic books, 5 trade books and more than 50 newspaper columns, op-eds and book reviews. His research has been highlighted in The Economist, the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, El Pais, Vanguardia, La Repubblica, the Frankfurter Allgemeine, NZZ, der Standard, der Spiegel, CNN, RTN, Swiss and German TV and radio.