14

Healthy or Harmful?

Several developments in Western democracies over the past decade have sparked worries about political stability. Standing out are the rise of radical political parties, heated polarization around questions of immigration, nationalism, or social liberalism, and – in some cases – attacks on democratic institutions. However, conflict and choice between clearly distinctive alternative ideas of how societies and economies should be governed are at the heart of democracy. Democracy needs competition and conflict. But where is the line between healthy and harmful conflict and polarization?

In this paper, Silja Häusermann and Simon Bornschier explain that an interpretation of today’s state of democratic conflict as chaotic, fragmented, or volatile is misleading. Rather, Western democracies are in a process of a fundamental restructuring of the main political dividing lines. Over the past decades a new social cleavage has been emerging between universalistic and particularistic ideas of social, economic, and political organization, between openness and closure. This conflict is rooted in social groups defined by education, occupation, and territory. It relates to underlying collective identities on both sides, and it will dominate democratic party competition for the foreseeable future. It is not per se harmful to democracy but reflects genuinely different visions of desirable social order. However, under certain conditions, it can turn on democracy itself.

The authors thus examine the functional and dysfunctional implications of polarized political conflict for democracy. To what extent is conflict and polarization healthy and under what conditions is it likely to endanger the very legitimacy and institutional stability of democracies? Building on existing knowledge about the dynamics of polarization, they discuss political and institutional means to contain polarization and to protect democratic stability.

Several developments in Western democracies over the past decade have sparked worries about political stability. Standing out are the rise of radical political parties, heated polarization around questions of immigration, nationalism, or social liberalism, and – in some cases – attacks on democratic institutions. However, conflict and choice between clearly distinctive alternative ideas of how societies and economies should be governed are at the heart of democracy. Democracy needs competition and conflict. But where is the line between healthy and harmful conflict and polarization?

In this paper, Silja Häusermann and Simon Bornschier explain that an interpretation of today’s state of democratic conflict as chaotic, fragmented, or volatile is misleading. Rather, Western democracies are in a process of a fundamental restructuring of the main political dividing lines. Over the past decades a new social cleavage has been emerging between universalistic and particularistic ideas of social, economic, and political organization, between openness and closure. This conflict is rooted in social groups defined by education, occupation, and territory. It relates to underlying collective identities on both sides, and it will dominate democratic party competition for the foreseeable future. It is not per se harmful to democracy but reflects genuinely different visions of desirable social order. However, under certain conditions, it can turn on democracy itself.

From consensus to polarization

Switzerland has long been seen as the prototypical case of a stable consensus democracy, characterized by moderate levels of party polarization and power-sharing institutions at the levels of elections (proportional electoral system), government (grand coalition), and territorial organization (federalism). And while the power-sharing institutions have (so far) largely remained in place, the Swiss party system has since the 1990s become one of the most polarized in Europe. Switzerland has also historically been no stranger to party polarization. Both the “Kulturkampf” between Catholics and Protestants, as well as the class conflict between the labor movement and the rightwing parties were particularly salient and contentious in the late 19th and early 20th century. It is only with the adoption of power-sharing institutions in industrial relations (“social partnership” from the late 1930s onwards) and in government formation (the “magic formula” adopted in 1959, including the four largest parties in the government coalition) that political conflict was moderated. However, this centripetal dynamic of conflict moderation and consensus-building eroded quickly from the 1980s onwards, when a very strong mobilization of new social movements on the left – leading to the emergence of green, left-alternative and feminist parties – was soon met with an equally successful mobilization on the far right. Hence, Switzerland was deeply affected by the new cleavage polarization already in the 1990s, with citizens and parties debating issues of gender equality, immigration, and European integration.

Switzerland has long been seen as the prototypical case of a stable consensus democracy, characterized by moderate levels of party polarization and power-sharing institutions at the levels of elections (proportional electoral system), government (grand coalition), and territorial organization (federalism). And while the power-sharing institutions have (so far) largely remained in place, the Swiss party system has since the 1990s become one of the most polarized in Europe. Switzerland has also historically been no stranger to party polarization. Both the “Kulturkampf” between Catholics and Protestants, as well as the class conflict between the labor movement and the rightwing parties were particularly salient and contentious in the late 19th and early 20th century. It is only with the adoption of power-sharing institutions in industrial relations (“social partnership” from the late 1930s onwards) and in government formation (the “magic formula” adopted in 1959, including the four largest parties in the government coalition) that political conflict was moderated. However, this centripetal dynamic of conflict moderation and consensus-building eroded quickly from the 1980s onwards, when a very strong mobilization of new social movements on the left – leading to the emergence of green, left-alternative and feminist parties – was soon met with an equally successful mobilization on the far right. Hence, Switzerland was deeply affected by the new cleavage polarization already in the 1990s, with citizens and parties debating issues of gender equality, immigration, and European integration.

Managing democratic polarization

How can societies deal with polarized programmatic conflict? Ideally, the political system produces policies, which entail compensation and foster compromises to maintain both effective governance and social peace. Such substantive pacification of political conflict via policies is, of course, seriously hampered in a context where the antagonism is strong and neither side is willing to give in. Hence, a certain moderation of conflict itself seems rather a precondition than an outcome to policy compromise.

At the level of society, integrative institutions such as strong public schools and universities can play an important role in fostering social cohesion. If such institutions run counter to political dividing lines, they foster multiple belongings of citizens and cross-cutting divides. Experiencing the “political other” in one’s social networks contributes to less hostile polarization despite pronounced programmatic differences. In this sense, any services and institutions that create integrative experiences across political divides – from good public transport to public media or well-maintained public spaces – may moderate affective segmentation.

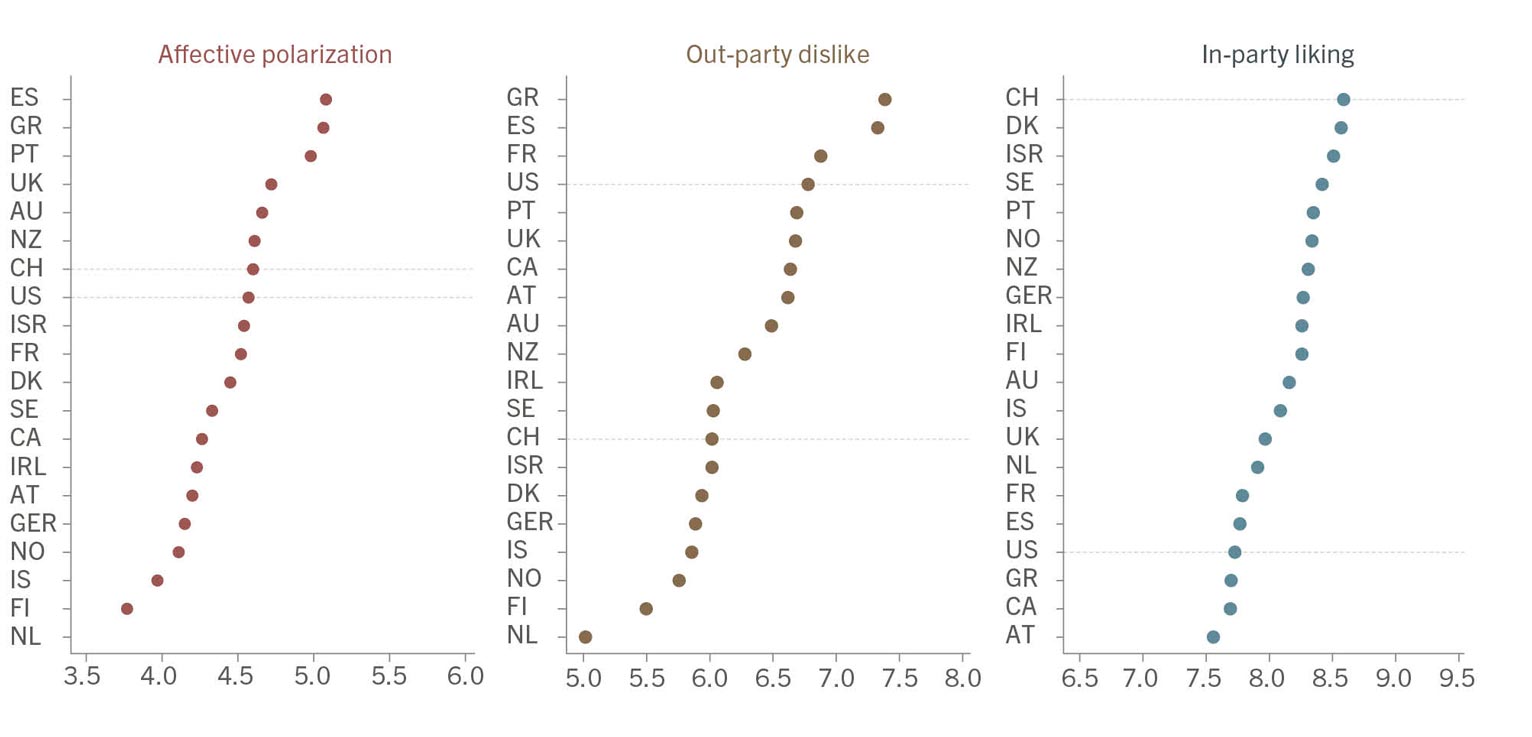

The contrast between Switzerland and the U.S. is instructive and illustrative in this regard. Both countries have reached similar levels of affective political polarization. In other words, political conflict is not only programmatic, but both sides have strong feelings when it comes to their own political camp and when thinking about those on the other side of the cleavage. However, affective polarization in the U.S. is strongly driven by “out-party disliking”, i.e. by negative feelings towards the “other side”, rather than by positive feelings about one’s own political party. By contrast, affective polarization in Switzerland is mainly driven by positive feelings towards the party voters choose in elections. The figure below shows this difference based on survey data measuring affect on standard “feeling thermometers”. The strong positive identification with one’s party in Switzerland has much to do with the multi-party system, allowing voters to identify quite precisely the political party that stands for their policy positions, while this choice is much more constrained in the U.S. two-party system. Beyond this, we can speculate that the lower levels of social, spatial and political segmentation in Switzerland help prevent strong negative affective dislike towards the “other side”.

How can societies deal with polarized programmatic conflict? Ideally, the political system produces policies, which entail compensation and foster compromises to maintain both effective governance and social peace. Such substantive pacification of political conflict via policies is, of course, seriously hampered in a context where the antagonism is strong and neither side is willing to give in. Hence, a certain moderation of conflict itself seems rather a precondition than an outcome to policy compromise.

At the level of society, integrative institutions such as strong public schools and universities can play an important role in fostering social cohesion. If such institutions run counter to political dividing lines, they foster multiple belongings of citizens and cross-cutting divides. Experiencing the “political other” in one’s social networks contributes to less hostile polarization despite pronounced programmatic differences. In this sense, any services and institutions that create integrative experiences across political divides – from good public transport to public media or well-maintained public spaces – may moderate affective segmentation.

Cross-national variation

These social dynamics in Switzerland are reinforced by political institutions that require and support the political integration of programmatic adversaries. The collegial grand coalition government may have become less effective in policy output and problem-solving, but it guarantees the integration of political adversaries and their commitment to the political system.

Contrast this with the majoritarian U.S. presidential elections, which are extremely contested. Even after one side has won the presidential elections, polarization continues and both sides try to block each other from achieving policy outputs. This frustration reinforces polarization and encourages attacks on the very institutions, especially when these are weak.

Finally, a word on technocratic government as a solution to political polarization and deadlock is in order. While technocracy – e.g., by means of caretaker governments or non-partisan technocratic governments – may seem a tempting “way out” of democratic polarization, it may yield returns on policy effectiveness only in the short run. When technocratic governments are formed in a context of crisis – think of Italy in between 2021 and 2022 under former President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi or the Monti cabinet that governed between 1993 and 1994 – populist parties tend to see their vote shares rise in the following elections. When polarization and programmatic conflict is real and rooted in society, it seems more promising to develop ways to integrate, rather than bypass it.

These social dynamics in Switzerland are reinforced by political institutions that require and support the political integration of programmatic adversaries. The collegial grand coalition government may have become less effective in policy output and problem-solving, but it guarantees the integration of political adversaries and their commitment to the political system.

Contrast this with the majoritarian U.S. presidential elections, which are extremely contested. Even after one side has won the presidential elections, polarization continues and both sides try to block each other from achieving policy outputs. This frustration reinforces polarization and encourages attacks on the very institutions, especially when these are weak.

Related videos

Authors

Silja Häusermann is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, where she teaches classes on Swiss politics, comparative political economy, comparative politics and welfare state research. Her research interests are in comparative politics and comparative political economy.

Simon Bornschier is the director of the research area political sociology at the department of political science of the university of Zurich. His research focuses on the formation and transformation of cleavages and party systems in Western Europe and South America, as well as the quality of representation.

Silja Häusermann is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, where she teaches classes on Swiss politics, comparative political economy, comparative politics and welfare state research. Her research interests are in comparative politics and comparative political economy.

Simon Bornschier is the director of the research area political sociology at the department of political science of the university of Zurich. His research focuses on the formation and transformation of cleavages and party systems in Western Europe and South America, as well as the quality of representation.